Last Updated on May 22, 2024 by Steve Weinman

The French diving pioneer made his name working with Jacques Cousteau but went his own way with one of many strings to his bow – painting deep blue seascapes while under water. His art didn’t always get the appreciation it does now, says JOHN CHRISTOPHER FINE, who believes that Laban was ahead of his time

In spring last year the late underwater artist Andre Laban was honoured at the Oceanographic Museum of Monaco with a special exhibition of some of his thousand-plus paintings – and this coming August and September another show is to be dedicated to his work, at the headquarters of aerospace company Thales Alenia Space in Cannes.

Laban was born in Marseille in 1928 and, after graduating as a chemical engineer in 1952, offered his services to Jacques-Yves Cousteau.

“What can you do?” asked Cousteau, who was not famed for his endearing personality early on his climb to fame.

“Nothing.” The 24-year-old’s frank reply struck a chord with Cousteau, who happened to be looking for an engineer to replace his associate Jan van Wooters.

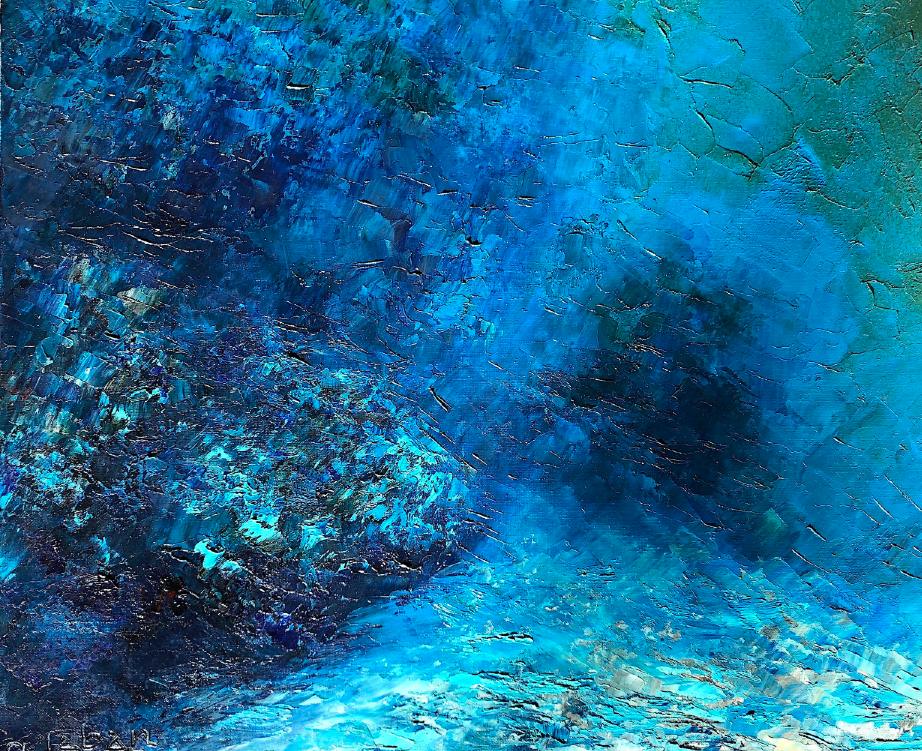

Laban, who had been captivated by the sea since he was 14, would work with Cousteau over the next 20 years, and in that time he not only experienced the underwater world but invented and engineered submersibles, cameras and housings and dive gear.

Under the moniker Labanus, he became one of France’s most notable pioneer divers. For 10 years from 1956 he was director of the French Office for Underwater Research, developing and piloting experimental undersea vehicles. He led a team of six that lived for three weeks at 100m on Cousteau’s Conshelf 3 habitat.

His vision helped to create the cameras and housings used to shoot The Silent World. He filmed for the Cousteau Odyssey TV series and won awards for his own films.

Painting beneath the surface

The young man had both engineering and artistic talent. He had started painting maritime and provincial landscapes in 1950, mastering realism and moving on to the school of French experimentalism that required the palette-knife to help convey what he saw.

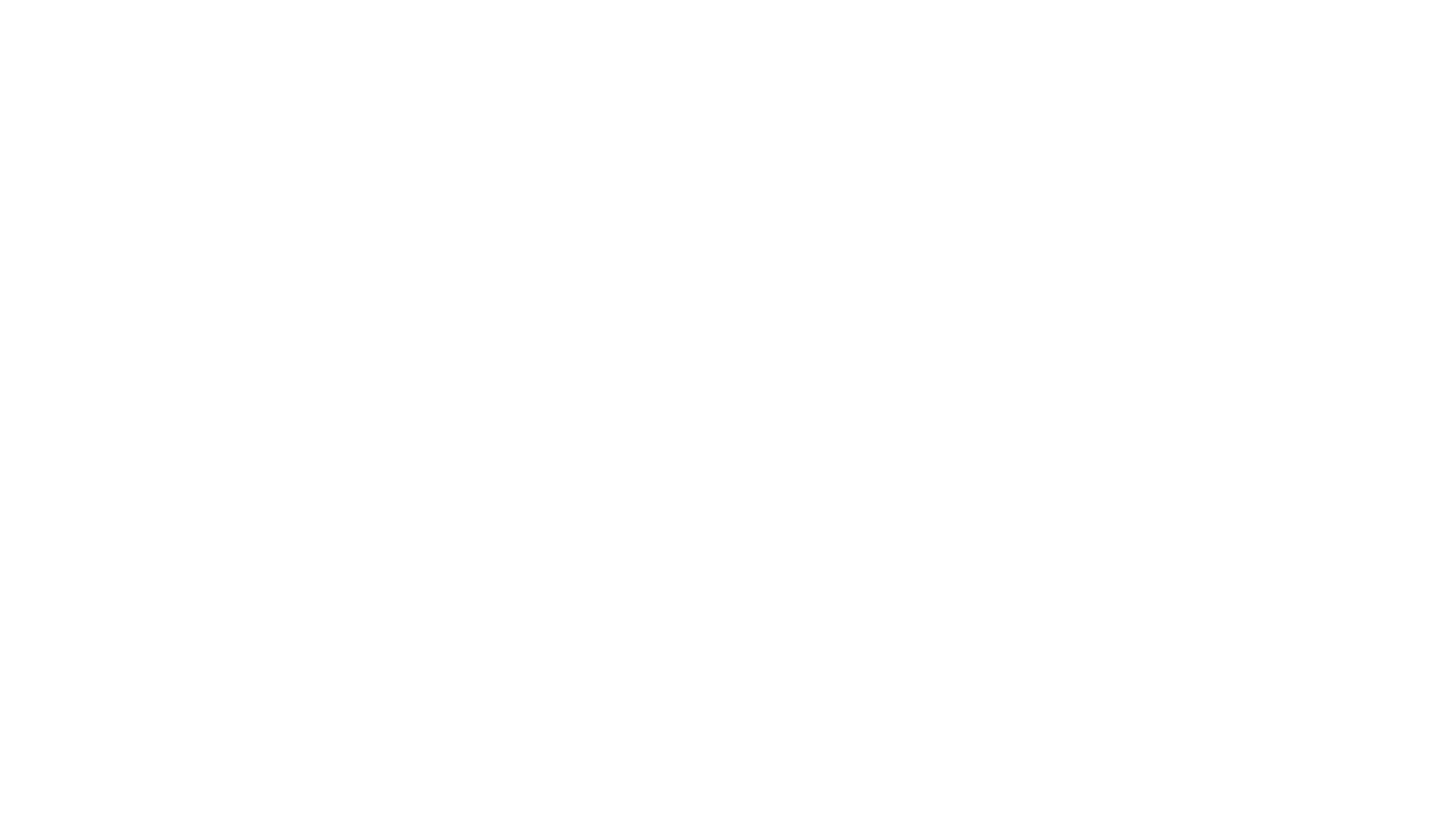

Soon enough, he was seeing blue everywhere. From the decks of Calypso, Cousteau’s vessel of exploration, in 1966 Laban began painting while under water the sights he saw, and those he imagined.

No one person can be said to have invented the idea of painting under water, but Laban was certainly the father of the technique. His canvases were coated with grease and oil paint thick enough to be worked with both knife and brush, usually at depths of 15-25m.

He made blue from blue with surrealistic and realistic modifications of what he saw on his dives. His models became the sea around him, and he would continue painting under water well into his mid-80s.

To outward appearances, Laban seemed shy, but his wry sense of humour became a trademark and, combined with his kind personality, made him loved and admired by fellow-divers.

Giving pictures away

The last time I saw him was in Antibes Juan-les-Pins during an international film festival. The festival organiser’s companion told me that Laban was scraping by, still selling his art but only enough to supplement his meagre resources.

His good heart usually meant that he gave away those underwater paintings that did not sell during exhibitions or festivals. The same grand mirth that twinkled in his eyes could also turn to sadness.

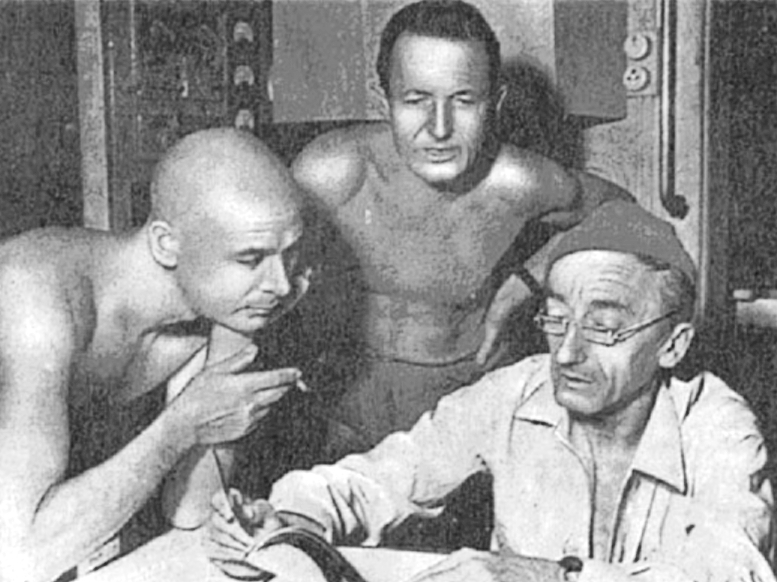

Philippe Tailliez was my long-time friend; his wife Josie came from a village near my own mother’s in Brittany, and I would stay with the couple in Toulon. We would work on his book and projects, and swim and dive in the cold Mediterranean.

Tailliez had been Cousteau’s superior officer in the French Navy, and had brought Cousteau into diving along with another friend, Frederic Dumas, so it was natural for Laban to take to him and offer him a painting, one layered in vivid and pastel blues, with Tailliez in profile looking down from one corner to a rolling wave. The wave seems to move.

After the festival, I was staying on to dive along the Mediterranean coast before joining Tailliez in Toulon on my way home to New York. Laban and I were together as he took down his paintings in the convention hall. He did not appear to have sold any at all but, although disappointed, his face was still animated, that happy-sad look in his eyes.

He offered me one of his works but, although I wanted it, I didn’t take it. It was not a rejection, rather a gesture of friendship that Laban understood, aware that he needed to sell his art, not give it away.

He invited me to visit him at Le Sous-Marin Bleu, his home at St Antonin Noble Val, in southern France but nowhere near the sea. However, work kept me away from international film festivals and I never got to his studio, and didn’t see Laban again.

What can only be described as a father-son relationship formed between Laban and young French art-lover Laurent Cadeau, who created Maecene Arts in Brive-la-Gaillarde, not far from Laban’s home.

Cadeau was not a diver when the two met, but his urge to see Laban paint under water did eventually get him diving. He later described his friend as “media character, scientist, experienced diver, photographer, film-maker, explorer, writer, poet, comedian, actor…”

Maecene Arts published several of Laban’s books, arranged exhibitions of his art and promoted the artist through TV and other media, and this collaboration did not end when Laban died on 10 October, 2018, in his atelier in St Antonin Noble Val. Art doesn’t die.

Laban never made a fortune from his work in diving, whether from his various inventions or his paintings, but he has left a legacy of work: landscapes that bring to mind Monet, curious curving modern paintings with a hint of Picasso and underwater paintings that remain a legacy for the world to inherit.

Find out more about Andre Laban’s paintings at Maecene Arts or email contact@maecene-arts.eu

Also by JC Fine on Divernet: Tales of diving’s true pioneers, Cayman coral problems in black & white, Sea turtles on the brink, Deep Doodoo: Diver’s-eye view of a Florida problem, Coral farmers reshaping the future, Sponges: Glue of the reef, A dive pioneer turns 80 on Bonaire