- 1) Q: You’re well-known as a technical diver, but what got you started in diving?

- 2) Q: What was the attraction of technical diving for you, and what was it like being involved in the mixed-gas deep-diving scene in its formative years?

- 3) Q: You pioneered deepwater shipwreck photography. What are some of the main challenges when you’re taking photographs in extremely deep water?

- 4) Q: You have dived famous wrecks such as HMHS Britannic, RMS Lusitania, ss Transylvania and mv Wilhelm Gustloff, to name but a few. Which hold a special place in your memories?

- 5) Q: As well as diving known wrecks, you are also a prolific wreck-hunter, notching up diving on a great many virgin shipwrecks. What have been your most memorable finds?

- 6) Q: You’ve dived open-circuit technical equipment and closed-circuit rebreathers. What do you see as the most important elements of your tech-diving arsenal?

- 7) Q: What has been your most-memorable moment in diving?

LEIGH BISHOP is one of the UK’s leading technical divers, pioneering deep-wreck photography and exploring many prestigious shipwrecks. Here he chats about what drives his interest in tech diving and wreck exploration, and what his future plans are

Q: You’re well-known as a technical diver, but what got you started in diving?

A: For as long as I can remember I had always wanted to be one of the best divers, but unlike most of my friends who were influenced by The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau, I can’t recall actually watching that. I do, however, remember seeing a frogman on television somewhere that stayed in my memory for years, fascinating me through childhood.

Before shipwrecks, there was caving. Having left school, I joined my local caving club and spent pretty much every weekend of the 1980s caving. In 1988 I was passing through Kingsdale in Yorkshire and spotted a scuba diver emerging from the famous Keld Head. Running down to him, I remember bombing the poor guy with 1,001 questions.

When he eventually took his hood and mask off, the diver turned out to be John Cordingley, a well-known and respected British cave-explorer of the time. John invited me back the following weekend to dive and, somehow, I mustered up some basic gear and drove back to Yorkshire, where I was to put a regulator in my mouth for the very first time.

I descended into an underwater world, a cave called Joint Hole, and swam quite some distance to a restriction. However, I recall being bitterly disappointed that I couldn’t continue further. I was 20 years old!

It wasn’t long before I was an active member of the CDG [Cave Diving Group], diving in caves all over Britain. It was also a link to meeting people who would remain diving friends for life.

I joined my local dive club, Thrapston and District Sub Aqua Club in Northamptonshire, if only to improve my knowledge and skills and become officially certified. After one pool session in the clubhouse, there was a conversation about a shipwreck the club intended diving that coming weekend – well, let’s just say the rest is history!

Q: What was the attraction of technical diving for you, and what was it like being involved in the mixed-gas deep-diving scene in its formative years?

A: My diving naturally evolved into what became known as technical diving around the same time as the editor of AquaCorps magazine, Michael Menduno, actually coined the phrase “technical Diving”. I had been using oxygen that I read was good for decompression but I didn’t understand why.

John Cordingley and his dive partner Russell Carter had returned from a cave-diving expedition in France supporting Swiss diver Oliver Isler, and explained the concept and benefits of mixed gas to me. There was no material to read on the subject, let alone any courses to enrol on, but luckily I got hold of one of Dr Bill Stone’s rare books about his Wakulla Springs cave-diving project in Florida.

The book opened up a world of mixed-gas diving, pioneered at the time by the US Deep Caving Team. I even remember the book had schematics for early mixed-gas rebreathers.

As a member of the CDG and always around the UK cave-diving hang-outs, I’d met Rob Parker at roughly the same time I was reading my new treasured material. Parker happened to be a lead scuba diver on that very project, and in return he introduced me to another pioneer of mixed-gas diving of the time, Rob Palmer.

By the early 1990s, the technical-diving revolution was about to take off and, diving from John Thornton’s boat in Scapa Flow, Palmer taught me one-to-one how to use mixed gas.

I was now armed with both the knowledge and diving equipment to explore deep shipwrecks that were previously off the radar, and John Thornton would be the man I would first do it with.

Q: You pioneered deepwater shipwreck photography. What are some of the main challenges when you’re taking photographs in extremely deep water?

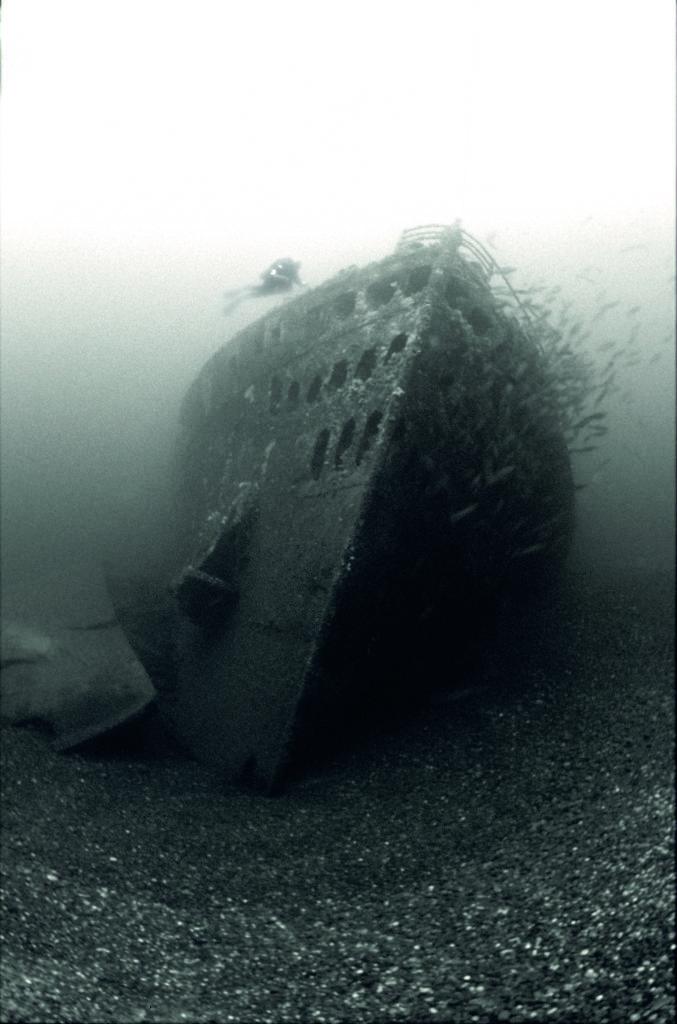

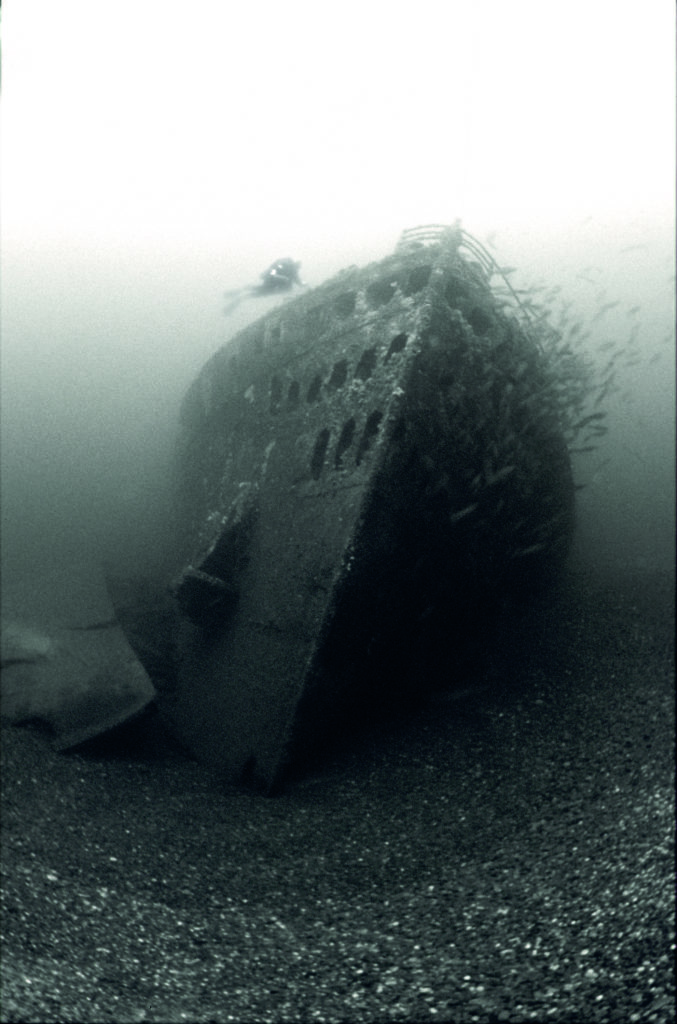

A: By the mid-1990s, I joined the UK’s first mixed-gas deep wreck-diving team, known as the ‘Starfish Enterprise’, headed up by Simon and Polly Tapson. Simon had taken photographs of the Lusitania at 93m, and the pair of us fantasised over the possibility of shooting a shipwreck beyond the 100m depth.

The only problem was that housings and strobes were only rated to 60m and our next project as a team was the Britannic, which we knew to be twice the depth rating of our equipment.

As naive as I was, I phoned up just about every well-known underwater cameraman for advice, even the likes of BBC Blue Planet cameraman Peter Scoones, all of whom told me I was in uncharted ground and couldn’t help.

I used Simon’s camera system on Britannic in 1998 and, if I’m honest, I simply kept my fingers crossed and hoped for the best.

I recall positioning myself on the seabed at 120m depth with the massive stern section of Britannic and her monster propellers impressively framed up just perfect in my viewfinder. Having set up the f-stop in relation to what I thought the shutter speed should be, I pressed the lever for the big money shot, only to fire off the entire 36 frames of film in less than a few seconds!

’if I’m honest, I simply kept my fingers crossed and hoped for the best’

The camera was like the sound of Duran Duran’s hit record Girls on Film with the noise of a photographer’s shutter rapidly operating. What had actually happened was that the depth was so vast, the pressure had prevented the lever from returning, resulting in the entire film being shot of blurred roll images showing me peering through the domeport with a confused facial expression!

Soon after that expedition, I found myself up in Malin Head with my mate Rich Stevenson trying to photograph the magnificent ocean liner Justicia. By now the Canadian company Aquatica had come to my rescue, with a housing that was rated to 100m.

My classic Sea&Sea YS 350 strobes were miraculously pushing on without so much as a murmur of a little white flag waving over the extreme depths we were now diving to. The only problem was that they were not powerful enough to light up huge sections of wrecks, despite being the daddy of Sea&Sea strobes.

To overcome the problem, I would focus my attention on time-exposure photography. Basically I would let nature do the lighting work for me. All I had to do was hold the camera dead still in order to prevent motion blur while the shutter remained open long enough for the light to make my image.

I approached the British Society of Underwater Photographers for my solution. Engineer and expert photographer Ken Sullivan came to the rescue, building me a system to attach my Aquatica housing to a heavy-duty tripod. Using fast black-and-white film, I was able to shoot the first time-exposure images of a deep shipwreck and thus showcase the magnificent world of previously forgotten ships for all to see.

Q: You have dived famous wrecks such as HMHS Britannic, RMS Lusitania, ss Transylvania and mv Wilhelm Gustloff, to name but a few. Which hold a special place in your memories?

A: Aside from the fact that, yes, I have dived some famous wrecks, ironically the one I love so much isn’t as famous – the Duke of Buccleuch, sunk in the English Channel off Littlehampton. The story of both her sinking and discovery as well as physically swimming across the decks is all so enchanting, making the thrill of exploring shipwrecks truly how my dreams were made as a young boy.

Sunk in 1889 and discovered in 1989, the holds of the Iron Duke are full of cargo destined at the time for Australia.

After surfacing from a dive, I always sit back, watch and listen to the beehive of activity among the divers on the boat. Each and every one has a story to tell one another of their dive to last the journey home. The divers all have smiles on their faces, and their stories are as enchanting as the wreck itself.

Q: As well as diving known wrecks, you are also a prolific wreck-hunter, notching up diving on a great many virgin shipwrecks. What have been your most memorable finds?

A: I can’t rule out the time Rich Stevenson and I became the first men to swim across the decks at 85m of the famous Flying Enterprise. The ship sank in 1952 and, other than the Coronation, became the media event of the year.

In a severe Atlantic storm, the captain remained on board and fought to save his ship for over two weeks before finally walking down the funnel as the ship gave in and eventually sank.

Captain Carlsen’s ship was there in front of our very eyes and I shot photographs of Rich in the same places as where the Captain was so famously photographed by media photographers in an aircraft circling the ship.

I found the maker’s plate on the front of the bridge – the ship’s birth certificate if you like – a beautiful piece of lettered brass that took pride of place in my office before I loaned it to Falmouth Maritime Museum, alongside other artefacts that were displayed for a number of years to the general public.

Another memorable discovery was the Kingsbridge, another enchanting shipwreck we discovered in 90m of water off Falmouth. Sunk in 1874 laden with 3,000 tonnes of colonial cargo, I found and recovered her bell, one of the most beautiful I had ever seen recovered from a shipwreck.

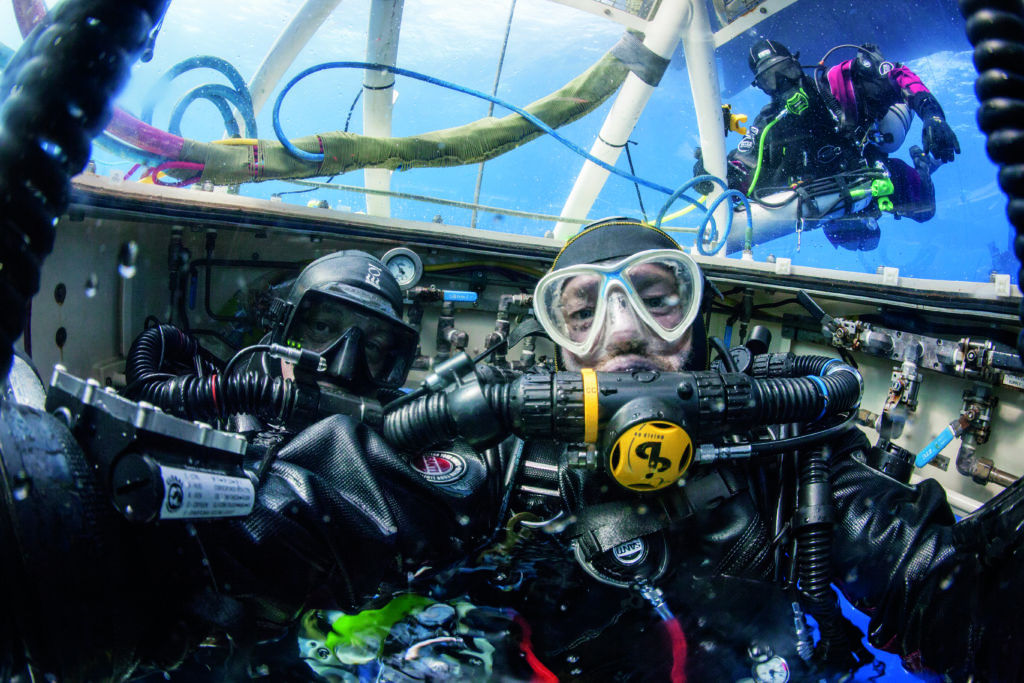

Q: You’ve dived open-circuit technical equipment and closed-circuit rebreathers. What do you see as the most important elements of your tech-diving arsenal?

A: I consider myself lucky to have lived in an era of pioneering shipwreck exploration but I see explorers of today as equally lucky, because they’re armed with far superior designed and functioning diving equipment than we were back in the day. Where was all this magnificent equipment when we actually needed it?

No advanced technical dive could be completed successfully without each and every component that a diver actually needs, making the question as to what I see as the most important elements of my tech-diving arsenal impossible to answer. Realistically, they all play equal roles.

While my AP Inspiration rebreather actually keeps me breathing way beyond 100m, my heated Santi drysuit keeps me from dying of cold if I’m in the Baltic Sea. I couldn’t progress through the pitch-black interior of a deep shipwreck without my powerful Light Monkey torch.

My Shearwater computer constantly updates my decompression profile, and a simple thing like my Kent Tooling reel is equally important to keep my whereabouts known to the skipper and surface team above.

Tough Miflex hoses knit everything together, and if it all went wrong and I had to bail out, I rely on Apeks regulators, which I know work perfectly even deeper than 100m!

Q: What has been your most-memorable moment in diving?

A: Circumnavigating Britannic with my dive partner Chris Hutchison in 1998! We breathed mixed gas from back-mounted twin 20-litre cylinders and cruised the decks on our ride-on AquaZep scooters. Britannic is the sister-ship to Titanic, but bigger and in one piece, a simply awe-inspiring sight!

I never thought that single dive would be surpassed by another, but on the 100th anniversary of the sinking in 2016, during the making of a BBC television documentary, it was done again but in true style and filmed.

With my close mates alongside me – Rich Stevenson, Italian Edoardo Pavia and, from Florida, shipwreck-hunter Mike Barnette – I again circumnavigated the entire 305m-long wreck aboard my modern Suex scooter in one dive.

Watched from one of two deep submersibles that followed and lit up the way, our friend Richie Kohler could only watch in awe at the fun we were having. The six hours of decompression was undertaken inside a bell that slowly moved us to the surface.

I called it the “Million Dollar Dive” and I question if there has been a better free-swimming scuba dive around a shipwreck ever to equal it?

Q: On the flip side, what has been your worst moment in diving?

A: Sadly, it was on Britannic seven years’ prior, during a filming project for National Geographic with the same friends. My great mate at the time, Carl Spencer, encountered problems at depth and never survived the dive.

It took a while to recover from that incident but I returned to the wreck in 2016 with the same guys and cracked on with it, as Carl would have wanted. There are, of course, other friends that have not surfaced from dives and all equally as sad. Each one I recall in a book about my diving adventures I hope to publish.

Q: What does the future hold for Leigh Bishop?

A: I always say that the single best thing about diving is the people you meet. The second is visiting corners of the planet that otherwise a sport such as football, rugby, netball or squash would never have enabled. The third is being able to make a little coin to make the process revolve around again and again.

With that said, the best times I’ve ever had and the best laughs are with the lads of the Darkstar deep wreck-diving team, headed up by the man I organise the Eurotek Advanced Diving Conference with, Mark Dixon.

Mark skippers his privately owned purpose-built dive-boat and his team quietly go about their business year after year, exploring deep shipwrecks around the British Isles.

I also have plans for a couple of exciting projects in the English Channel with renowned Weymouth skipper Graham Knott, one historic and one a wartime loss. Let me keep my fingers crossed on those and hopefully you will read about them in future editions of Scuba Diver.

Photographs courtesy of Leigh Bishop

Nice Doxa!