JOSS WOOLF takes a chance on behalf of others to undertake a more-adventurous-than-usual group liveaboard trip – but would she be taking the blame or enjoying the credit?

IN THE MIDDLE OF the southern Egyptian Red Sea, half a mile apart, you will find Big Brother with its lighthouse, built by the British in 1883, and Little Brother. It’s a very isolated pair of rocky outcrops.

Nobody lives there, but occasionally there is a military presence. In days gone by, as a punishment for some misdemeanour, the hapless victim would be made to swim from one island to the other across the “shark-infested” waters.

Two years ago I was handed the baton of running a time-honoured annual British Society of Underwater Photographers Red Sea dive-trip, begun by John Bantin many years ago, then continued by Linda Dunk and for at least the past 15 years by Jan Maloney.

Today our group’s ages range from the innocence of 32 to the wisdom of 82.

We are all underwater photographers of varying aspirations and have enjoyed travelling together for a number of years.

Our usual itinerary has been in the north incorporating, weather permitting, the wrecks at Abu Nuhas, the Thistlegorm, Jackson Reef and the inimitable Ras Mohammed with Shark Reef and the wreck of the Yolanda. Occasionally, for a change, we have ventured further south to the caves of St John’s and Fury Shoal, but the Brothers have never been on our agenda.

This was partly because they were closed to the public on and off for a number of years, but also because the rather more challenging diving did not appeal to everyone.

This time, with a good chance of seeing threshers, hammerheads and oceanic whitetips, I thought I’d lead the group astray and take the opportunity to pay the sharks a visit.

There were 22 of us aboard Hurricane, one of the Tornado Fleet operated by Scuba Travel, and winner of this year’s DIVER Liveaboard of the Year award.

AFTER AN EVENTFUL WEEK at St John’s, with its alluring cave systems and frequent Napoleon wrasse encounters, we said our goodbyes to half the group.

One day later, with a fresh batch of excited guests all happily installed, check-out dives completed and gin supplies replenished, it was time for the 12-hour night crossing to the Brothers, something I wouldn’t choose to do again in a hurry

With very strong winds and rolling seas it was probably one of the worst sea journeys I have ever experienced on a dive-trip.

Two sets wooden doors in our cabin banged loudly all night long; you had to cling to the sides of your bunk to avoid being thrown to the floor, and you knew that any attempt to get out of bed to rectify the position would set off the nausea to which many of us would inevitably succumb.

Combine that scenario with the customary gippy tummy, consistent with almost any Red Sea trip, having given priority to my stomach while kneeling face-down over the toilet…

I will say no more!

How our captain and crew managed to moor the boat safely, in the dark at 3am amid the lashing waves and howling wind, with six rope-lines to be secured to submerged moorings, remains a mystery to me and a credit to them.

Although the journey did take its toll on the number of willing divers that first morning, those who did manage to surface at 5.30am were well rewarded by a very close encounter with a huge thresher shark. Of course, that group did not include me.

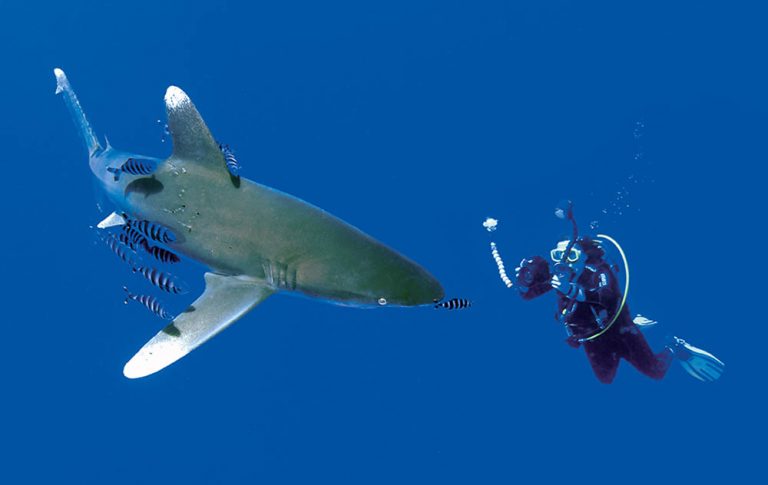

However, I felt sufficiently recovered by late morning to embark on the second dive of the day. We had already seen two oceanic sharks circling the boat from above decks. Once we had slipped in, with absolutely no current, clear blue water and sparkling sunshine, we had the kind of encounter you only dream about.

No fewer than three oceanics, each with their delightful entourage of pilotfish (pity they were blue and not yellow, but you can’t have everything, can you?).

For the entire dive, they continued to cruise among us.

Nobody even had to move for that perfect shot from almost any angle; all we had to do was wait until it was our turn for the fly-past.

It took me back to more than 20 years to my first visit to Elphinstone with my dive-club. Still spooked by the legacy of the film Jaws, I had been very nervous about the possibility of an encounter with a “dangerous” oceanic whitetip called Sid, into whose territory we were about to descend.

The dive-guides had told us all to wait, fully kitted, on the back of the boat while they checked out the site to make sure it was safe. After 20 minutes they still hadn’t returned, and we, or rather I, took an executive decision to jump in.

You can only imagine the shock I felt to find Sid immediately beneath the boat.

Our helpless guides were waiting on the seabed and we had no choice but to descend as quickly as possible and join them, where we remained for the rest of the dive.

I can remember, within the confines of our small plateau, finding a cluster of baby nurse sharks under a large, low-lying table coral and a couple of stonefish

I would not otherwise have noticed.

Sid didn’t go away; other groups of divers came and went but at some point we all had to come up and, of course, we are all still here to tell the tale.

THE POINT OF THIS ANECDOTE is to compare the absolute fear we felt about oceanics – indeed, any sharks – at that time with the sheer pleasure of being in their vicinity today. Of course, one must not be complacent; there have been one or two fatal incidents.

Our entertainment was curtailed only by the exhaustion of our air, but there were many smiles on peoples’ faces after that dive and lunch was a very noisy affair. The sharks remained aloof for the rest of the day, sadly, but we had already been lucky.

There are a couple of pretty good wrecks on Big Brother, not far from the Lighthouse. The Aida 11 was an Italian ship that was carrying troops when it collided with Big Brother one night in 1957. With its shallowest point at only 15m, it is a large, relatively intact wreck.

However, although the current is often strong, the soft corals are beautiful and the wreck attracts an abundance of marine life and offers great photo opportunities.

The Numidia, a former British 130m cargo ship, sank on only its second voyage, bound for India, in 1901.

The vessel, which now lies almost vertically between 8 and 80m, was carrying locomotive wheels, and these can still be found. However, its sheer depth makes it generally inaccessible to the recreational diver.

Accessible only by RIB, at the opposite end of the island, we rolled in for another opportunity to see the elusive thresher shark. Very annoyingly, one managed to cruise beneath all of us without being seen by anyone except Ahmed, our guide, and BSoUP Chairman Paul Colley!

A single manta ray did venture into our field of vision before we drifted around the corner over a fabulous coral garden with enough vivid orange female anthias to populate the entire Red Sea.

When you press the shutter the strobes make them all cluster tightly to the reef, so you press the shutter again quickly for a denser aggregation of colour.

I recall that, on a trip to the Seychelles a few years back, our lovely dive-guide, a former GP from Yorkshire, told me that the ratio of female anthias to males was about 10 to one, a statistic which, she said, rather mirrored that of the human situation on Mahe where she lived.

WE HAVE GROWN accustomed to the pattern of the weather; waking up to strong winds, a big swell and waves crashing over the top of the dive-deck, gradually abating during the day. The morning of the day we were to dive Little Brother is no exception.

During the night, two more boats have arrived, the crew of one of which is struggling to find some moorings. How those wooden-hulled boats seem to toss relentlessly about – I’m glad of the much more stable steel hull of Hurricane.

The early-morning dive is intended to give a greater opportunity of seeing the threshers, but at 5.30 we seem to be amid 40 cycling novices who all have the same idea! So, no sharks this morning but still a beautiful scenic dive with barracuda, shoals of bannerfish, dozens of needlefish and lots of cleaning and feeding activity.

Making our way around the reef, we soon hit a wall of strong current that forces us back. There are now so many divers in the water that we can’t see the fish for the bubbles.

I have decided to head back towards the boat and end the dive when an oceanic flanked by pilotfish emerges from the gloom. We try to follow it, but it soon disappears and we wait patiently under the boat for it to return. It doesn’t, so eventually I give up and try to make my way to the back of the boat.

THE CURRENT HAS picked up, and it’s quite a struggle to reach the ladders, which are now rising and falling violently, in unison with the swell of the sea.

At last I manage to get a hold and start my way up when an unexpected Chinese face tells me that I am on the wrong boat!

Oh, no! Will this mean that I have to pay the penalty of one ice cream to each of the crew?

What it does mean is a long hard swim against the current, dragging along an unwieldy camera. I can see other members of our group clinging on to anchor-lines like windsocks, but decide to make a go for it (I am a BSAC diver!) and swim to the ladder.

I am now quite out of breath with all the heavy finning, but at last the stern-line is almost within my reach.

It is only 6in away, but it still takes another dozen or so good kicks before I am able, finally, to grasp it.

I hold on for a while to recover my breath. The ladder is only 4ft away, but I cannot reach it. The crew toss me a line and, finally, they pull me back to safety.

“I am alive,” I declare, once back on board with a cup of hot chocolate in my hand. Funny, but the very same words are uttered by the next diver to emerge.

One of the crew points out a RIB in the far distance. To my astonishment, it turns out to be one of our own. The sudden strong current has swept some of our group and their guide so far away that it is only thanks to the eagle eyes and quick wit of our experienced crew that they are now safely back on board.

They saw a lot of sharks in the open water before they were picked up.

All too soon, our time at The Brothers is over and it’s time to head back to port via Elphinstone. The weather is closing in anyway, and our window of opportunity has now passed.

Unlike our journey here, the wind will now be behind us all the way. We have been incredibly lucky.

FACTFILE

GETTING THERE: Joss’s package included direct flights from Gatwick to Marsa Alam on Thomson, with a mid-week departure. The airport is close to the port where Hurricane is moored.

DIVING & ACCOMMODATION: Hurricane can carry 22 guests in 11 en suite twin cabins, four on the main deck and seven on the lower deck. Up to four dives per day, with free nitrox.

WHEN TO GO: The group went in June. The hottest time of year is July and August with temperatures of 30°C-plus but you can go at any time of year – just adjust wetsuit thickness accordingly.

MONEY: On board, you need money only at the end of the trip to settle your bar bill and for tips. You can use dollars, euros, sterling or credit card.

PRICE: Before discounts the trip cost £1295pp (checked in 2019) but as the group booked the entire boat discounts were applied. Visit Scuba Travel website for latest pricing.

VISITOR INFORMATION: Visit official Egypt Travel website