Australian diver NIGEL MARSH has been exploring the Great Barrier Reef for 40 years – and he won’t take those apocalyptic reports lying down

RISING UP THE WALL, I entered the shallows to find extensive and spectacular coral gardens. All around me, as far as the eye could see, were beautiful and healthy hard corals – staghorns, plates, brains and many other varieties.

Adding to this underwater garden of paradise were countless reef-fish, schools of fusiliers and a lingering whitetip reef shark. For the next half-hour I explored this coral jungle, marvelling at the intricate and diverse coral structures.

From this description, you might think I was exploring a remote part of Indonesia or Papua New Guinea, but I was diving the Far North section of the Great Barrier Reef, an area that is reported to be dead from coral-bleaching if you believe everything you read.

I first visited the Great Barrier Reef in 1978, and have since dived this natural wonder of the world many times.

Over that period of time the GBR has experienced five major coral-bleaching events, the past two over the previous two southern-hemisphere summers.

While the great majority of the reef south of Cairns was largely unaffected by the coral bleaching, the Far North section was reported to be severely hit by both events. This area, also known as the Far Northern Reefs and north of the popular Ribbon Reefs, is remote and visited by charter-boats only between October and December, when the weather is calm.

After the first coral-bleaching event in 2016 very mixed reports came from this region. Scientists were reporting that a quarter of the corals were dead, while the dive operators found little evidence of dead corals on reefs they visited.

With the Far North the richest part of the GBR, and one of my favourites, I was keen to see the true extent of the bleaching for myself, especially after the second event hit the region.

I joined Spirit of Freedom on a week-long expedition last October.

ARRIVING IN CAIRNS

I first wanted to check out the local reefs. With old mate and Cairns local Stuart Ireland I had a day-trip with Down Under Dive on its fabulous dive-boat Evolution.

The diving off Cairns is belittled by many divers, who have often never dived there but consider it cattle-truck diving and assume that too many divers have ruined the reefs.

The day-boats are large, taking more than 100 people, but most are snorkellers or people doing an intro dive, and on average only a dozen qualified divers will be in the water. In the past I have found that the reefs show little damage from visiting divers, as crews enforce their no-touch policy strictly.

We headed to Saxon and Hastings reefs, both on the outer reef. The weather wasn’t the best after several days of large seas and stormy conditions, but we still enjoyed 10-15m visibility.

We did three dives at two sites and saw mainly healthy hard corals. There were a few dead ones, but no more than usual on a typical reef in this area.

Later Stuart, a marine biologist who dives the reefs off Cairns regularly, told me that the bleaching was worst on the inner reefs, and most of the coral quickly recovered.

He added that new growth was evident on many of the worst-affected reefs.

Supporting his observations was a recent report from the Australian Institute of Marine Science, which found that reefs between Cairns and Townsville had recovered more quickly than expected and were showing signs that they were going to reproduce, two to three years earlier than previous studies had shown after coral-bleaching.

Stuart and I next headed to Cairns airport to fly to Lockhart River to meet Spirit of Freedom. This charter flight is part of the trip and took us 370 miles into the heart of the Far North.

Following a bus and tender transfer, we settled into our comfortable en-suite cabin on the luxury 37m liveaboard.

Most of our fellow-passengers were from Australia, but there were also Americans, Canadians and a few expat Europeans. For most it was their first trip to this region, and for a few their first time on the GBR.

Overnight we headed north, arriving at Southern Small Detached Reef in the morning. This isolated reef rises from deep water and we moored at a site I had dived before, Auriga Bay.

I was eager to see the state of the hard corals, as this site used to have pretty coral gardens on a sloping reef.

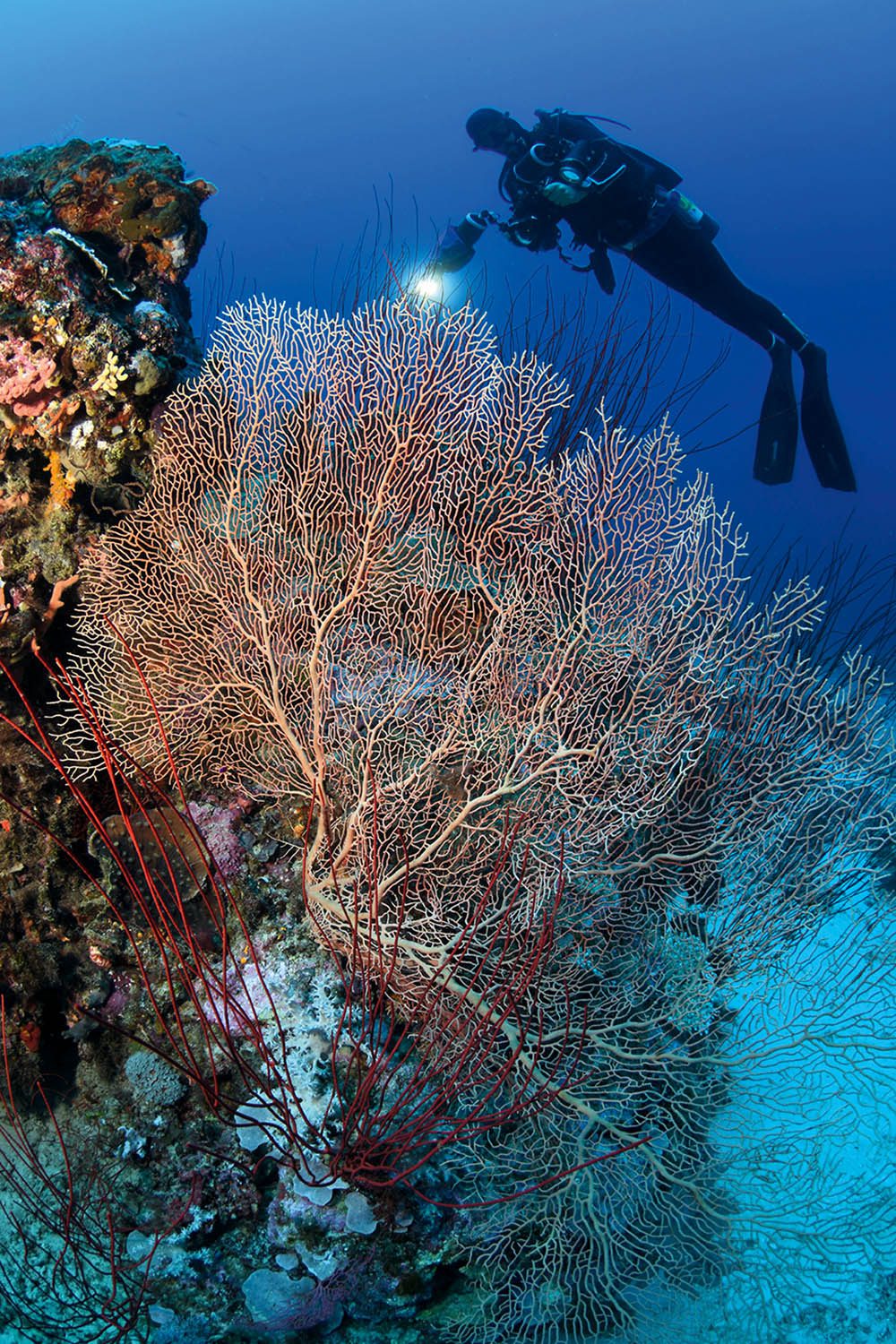

Descending the wall we saw lovely gorgonians, soft corals and pelagic fish, and once in the coral gardens I was happy to see that most of the hard coral looked healthy, though I was sad to see a wide patch that used to contain staghorn coral in ruins.

The cause was not bleaching but damage from the cyclones that occur every year in this part of Australia.

Northern Small Detached Reef, our next port of call, was a brilliant dive. There was not a lot of hard coral to be seen, because this reef plummets from the surface straight to deep water, but we explored ledges and overhangs, and saw walls covered in gorgonians, soft corals and whip corals. We also had our first shark encounters, getting buzzed by a grey reef shark and a silvertip shark.

We ended the day at another site I had dived before, Black Rock at Mantis Reef. Skipper Tony Hazell informed me that the boat hadn’t visited this site in two years, because the last time little had been happening.

Well, it was going off today, with schools of barracuda, trevally, snapper and surgeonfish. There were also lots of sharks – grey reef, whitetip reef and a few silvertips. Visibility wasn’t the best, so photography was limited, but we explored the sloping wall to see lovely corals, Maori wrasse, coral trout and even a spawning granulated seastar.

THE NEXT DAY we dived a site new to me, a coral outcrop near the Stead Passage called Well Worth It. Washed by the sort of strong current typical in the area, we explored a series of caves and ledges coloured by exquisite soft corals and gorgonians in deeper water.

Here we were surrounded by schools of rainbow runners, barracuda, fusiliers, snapper, surgeonfish and trevally. We also saw grey reef sharks, mackerel, gropers and a huge dogtooth tuna.

From the deeper parts of the reef we headed into the shallows to find the acres of wonderful hard corals mentioned in the introduction.

This dive was so good that we did it again, and one lucky group had a close encounter with a small whale shark.

With much of the Far North unexplored, we also did a few exploratory dives, starting on a wall near the Five Reefs that we nicknamed Stella.

Exploratory dives are always a risk, but in this area it’s hard to find a dud. This site once again had lovely hard corals in the shallows and large gorgonians in deeper water. It also had many ledges and caves, where I found the best collection of pink lace corals I have ever seen, plus a very large tawny nurse shark.

OVER THE NEXT FEW DAYS we explored Wood Reef, Great Detached Reef and Three Reefs, and all had healthy hard corals. A report from the ARC-CRS that 26% of the corals in this area were dead was plainly not accurate on the sites we dived, as I was only seeing 5% dead coral at most.

However, this report was based on an underwater survey of only 83 reefs.

A highlight was the Pinnacle and Deep Pinnacle at Great Detached Reef. Both these pinnacles rise from deep water and are coated with beautiful soft corals, whip corals, sponges and gorgonians.

While populated with a good variety of fish and sharks, the macro life was the big attraction for me, with nudibranchs, flatworms, anemonefish, hawkfish, leaf scorpionfish and many other species.

The Pinnacle was also a brilliant night-dive, featuring octopuses, lionfish, a hunting cone-shell and numerous sea-slugs. The richness of these pinnacles is more reminiscent of sites in PNG than other parts of the reef.

After lunch on day five we headed to one of the main attractions in this area, Raine Island. This remote coral cay is the largest and most important green turtle nesting site on the planet, and not a bad place to dive.

Since my last visit, much of the adjacent reef had been designated off-limits, so we could dive only the exposed eastern end of the reef.

On two amazing drift-dives we saw dozens of turtles. many very shy as they rarely see a diver. We also encountered a mating pair that unfortunately uncoupled as soon as they saw a group of divers staring at them.

The turtles were wonderful, but it was great to see the hard corals looking very healthy. Pounded by ocean swells, these were mostly short, squat and densely packed. In the many caves and ledges we encountered reef sharks, pelagic fish, an ornate wobbegong and several small epaulette sharks.

Overnight, we voyaged to the southern section of the Far North to spend a day diving Creech, Joan and Wilson reefs, and once again we saw mainly healthy hard corals, and only a limited number of dead corals. The exploratory dive at Joan Reef was eye-popping, with the greatest collection of plate corals I have ever seen, some more than 3m wide.

Now called Plates On Parade, this site was also home to vast schools of fish, and will likely become a regular fixture on future trips to this area.

FOR OUR LAST DAY’S diving we headed south overnight to dive the Ribbon Reefs. Parts of this popular liveaboard destination were hit by coral-bleaching, especially around Lizard Island, but the corals in this area have seen more devastation from several cyclones over the past few years.

As Tony explained, if a dive-site is cyclone-damaged it’s left for a couple of years to give it time to regenerate. Spirit of Freedom also finds new sites, such as Google Gardens.

Exploring these lovely hard-coral gardens makes you wonder how some sites are spared cyclone damage and others nearby are destroyed. Exploring a network of canyons, we marvelled at the delicate hard corals and admired the numerous reef fish.

Google Gardens is also a good spot to see broadclub cuttlefish, and everyone saw a few except for Stuart and me, as we had headed in the wrong direction.

OUR FINAL DIVE was at one of my favourite GBR sites, Steve’s Bommie. It was six years since my last visit, and Tony warned me that it had changed, suffering a double blow from cyclone damage and coral-bleaching.

It was a sad sight, the lovely soft corals missing and much of the hard coral dead, but the bommie was still home to an impressive variety of fish and invertebrate species, including schools of trevally, snapper and goatfish.

We also saw nudibranchs, leaf scorpionfish, pipefish, pufferfish, boxfish, mantis shrimps, nudibranchs and numerous stonefish.

The other divers thought it was incredible, but it was only a shadow of its former self. However, the crew said it was already showing signs of recovery.

That night we enjoyed a great barbecue under stars (the food on Spirit of Freedom is always sensational) before heading back to Cairns.

My fellow-passengers, especially the ones from overseas, couldn’t believe how healthy and lovely this section of the Great Barrier Reef was, some saying that they had come only because they thought it was their last chance to see the reef before it died.

The obituary for the Great Barrier Reef might already have been written, but this natural wonder of the world is far from dead, and the Far North is alive and well.

Coral-bleaching occurs when the coral is stressed and loses the symbiotic dinoflagellates that live within the tissue of the hard coral. This algae supplies the coral with energy and, when lost, leaves it looking white.

Various factors can cause the loss of this algae, including an influx of fresh water, but a rise in water temperature is the most common factor. Fortunately the coral can recover if the water temperature doesn’t remain too high for too long.

In recent coral-bleaching events on the GBR, coral mortality varied from 1% on the South section to 67% on the North section, according to the ARC Centre of Excellence Coral Reef Studies.

The GBR is not the only coral reef to suffer from coral-bleaching over the past few decades, and many around the world are in far worse shape.

In the north the situation was a lot worse, with 67% mortality in the North section and 26% in the Far North.

But in-water reports from dive operators indicate that the bleaching was mainly on inshore reefs, those that have been affected by water-quality issues for decades due to agricultural runoff.

Water quality has been a major issue affecting the health of the reef for a long time, as the coastline adjacent to the reef has been developed for agriculture, tourism, industry and residential housing. This has seen the destruction of forests and mangroves and an influx of soil and chemicals into rivers.

The health of the reef has also been affected by outbreaks of crown-of-thorns starfish and regular cyclone damage. And with climate change, things can only get worse.

The Australian government needs to do more to protect the GBR’s future, ensuring that water quality is improved, no new coal-mines are approved and more patrols are set up to stop illegal fishing.

The Great Barrier Reef is on the road to recovery from the recent coral-bleaching events, but who can say what the future holds?

The Big Picture

The Great Barrier Reef is more than 1400 miles long and comprises more than 3000 individual reefs. Water temperatures across the reef can vary up to 5°C.

Recent coral-bleaching events have mainly affected reefs in the north, with the southern half of the reef (south of Port Douglas and where the great majority of reef-tourism is based) showing either little evidence or little effect from the bleaching.

This was backed up by a report from the ARC-CRS that showed only 1% coral mortality in the South section and 6% in the Central section.

FACTFILE

GETTING THERE: Cairns is regularly serviced by domestic flights in Australia on Qantas Jetstar and Virgin Australia, and on international flights from many countries. A visa must be obtained before departure.

DIVING & ACCOMMODATION: Spirit of Freedom is one of only a handful of charter boats that visit the Far North and generally offer several 7 day-trips each year.

WHEN TO GO: The Far North is visited by liveaboards only in October, November and December, when water temperatures are 26-28°C. Visibility is generally 15-30m.

MONEY: Australian dollar

PRICES: You pay from $5045pp (depending on cabin) for seven nights on Spirit of Freedom, with 24-26 dives, meals, wine & beer, transfers and marine-park fees.

VISITOR Information: Queens Land Website – Travel to Australia Website