TECHNICAL DIVER

The Technical Diving Revolution – part 2

Last month US diver MICHAEL MENDUNO recalled the emergence of what would become technical diving. Now he looks at how it got its name, at the controversy generated by the ‘devil gas’ nitrox, and the battle to get to grips with safety in the early ‘90s. Main picture courtesy of LEIGH BISHOP

Also read: Guz tech divers set up winter date

ONE OF THE PROBLEMS in the initial days of tech diving was that almost all of the diving was “in the closet.” It wasn’t widely talked about or written about in the diving press, or discussed at dive-industry forums such as the Diving Equipment and Marketing Association (DEMA) show.

It was understood that if you were doing this kind of diving you kept it to yourself, lest you be blamed, shamed or, worse, get someone hurt.

There was no forum to exchange information and ideas, and there were no training courses. Unfortunately the lack of information made divers less safe!

I started aquaCorps Journal in January 1990 to change that. Our initial tag line was “The Independent Journal for Experienced Divers”.

I had begun doing relatively deep (45-60m) decompression dives in California in the late 1980s with a citizen-science group out of Silicon Valley called the Cordell Expedition. It conducted biological survey studies on the sea-mounts off the Big Sur coast.

I was so excited about the dives and what we were doing that I wanted to write about it, and approached a number of dive magazines. No one would touch it.

Eventually a California-based magazine called Discover Diving agreed to publish my article, but not without caveats and warnings on every page that this was not recreational diving.

I was also introduced to cave-diving, and got a copy of Bill Stone’s 1987 book The Wakulla Springs Project, which absolutely blew my mind: “You can do that?”

In that first issue of aquaCORPS we featured an article by Dr Bill Hamilton headed Call It “High-Tech” Diving.

We also referred to it as “advanced” and “professional sports” diving, a moniker invented by marine biologist and early rebreather pioneer Dr Walter Stark, inventor of the first production electronic closed-circuit rebreather, the Electrolung.

At the time, we didn’t really know what to call this new form of sport-diving that cut across traditional sport-diving communities. None of the names seemed to work.

It was also clear that we needed to establish this form of diving as separate and distinct from recreational diving.

‘Safety is the key consideration in diving. It entirely controls depth and time capabilities.’

Jean-Pierre Imbert

THE RECREATIONAL diving industry was not happy that deep and decompression diving – the “D-words” – were out of the closet, and didn’t want to have anything to do with what was emerging.

People were rightly concerned that an increase in diving fatalities would trigger US government intervention and remove the recreational diving industry’s exemption from Occupational Safety & Health Administration (OSHA) standards. UK divers had similar worries about increased Health & Safety Executive (HSE) regulation.

At that time, I had several friends who were rock-climbers and involved in what was then called “technical climbing”, in which individuals used ropes and protection to tackle rock-faces that could not otherwise be climbed.

The word “technical” had all the right connotations. I even imagined that “technical dives” might one day be rated by degrees of difficulty and/or exposure, in the way that climbers graded rock climbs, for example a 5.11 climb, using the Yosemite Decimal System (YDS) developed by the Sierra Club.

So I pinched the term for diving. I used “technical diving” for the first time in aquaCorps #3 Deep, published in January 1991. In the following issue I changed aquaCorps’ tagline to “The Journal for Technical Diving.”

We also launched a companion newsletter called technicalDiver.

Later that year Drew Richardson, then a vice-president of the Professional Association of Diving Instructors (PADI), penned an editorial: Technical Diving – Does PADI Have Its Head In The Sand?” for PADI’s Undersea Journal.

This helped to legitimise tech diving, as distinct from recreational diving. And the name stuck! Contrary to popular belief, PADI was not out to shut down tech diving, but it did want to distinguish it from recreational diving.

WE CALLED IT the “technical diving revolution” but the revolution was really about adapting mixed-gas technology to the consumer market.

The concept was simple and brilliant: you could improve divers’ safety and performance, enabling them to extend their depth and bottom-time, by optimising their breathing gas for the planned exposure.

In this case optimising meant:

1) Maintaining efficient and reliable oxygen levels over the course of a dive;

2) Reducing/eliminating undesirable inert gas effects such as narcosis and HPNS (High-Pressure Neurological Syndrome) and facilitating off-gassing;

3) Reducing breathing-gas density to minimise the work of breathing and prevent CO2 build-up.

As such, mixed-gas diving also represented a powerful paradigm shift for the sport-diving community. As author Neil Postman wrote in his book Technopoly: The Surrender of Culture to Technology: “New technologies compete with old ones – for time, for attention, for money, for prestige, but mostly for dominance of their world view.”

Overnight the emergence of technical diving, made possible by the use of mixed-gas technology, turned the recreational diving world on its head.

While PADI “deep divers” were cautiously edging their way down to their 40m depth limit, many tech divers were ascending to that depth to pull their first decompression stop.

Needless to say, recreational diving instructors no longer represented the apex of the sport-diving foodchain.

In addition, while once considered the mark of the elite, diving beyond 67m on air was considered increasingly foolish.

As Woodville Karst Plain Project (WKPP) co-founder Bill Gavin said of deep-air record diving: “It’s like setting the Bonneville Flats speed record while drunk. What’s the point?”

Of course, mix technology was not being promoted only for technical divers. In addition to use by the emerging tech community, Dick Rutkowsky, a former aquanaut, deputy diving director for the National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), founder of the International Association of Nitrox Divers (IAND) and co-founder of American Nitrox Divers Inc (ANDI), began promoting the use of nitrox for recreational diving.

And he was colourfully recalcitrant in his advocacy. “Diving on air is like having sex without a condom. The technology is there. It’s stupid not to use it,” Rutkowsky offered at the time.

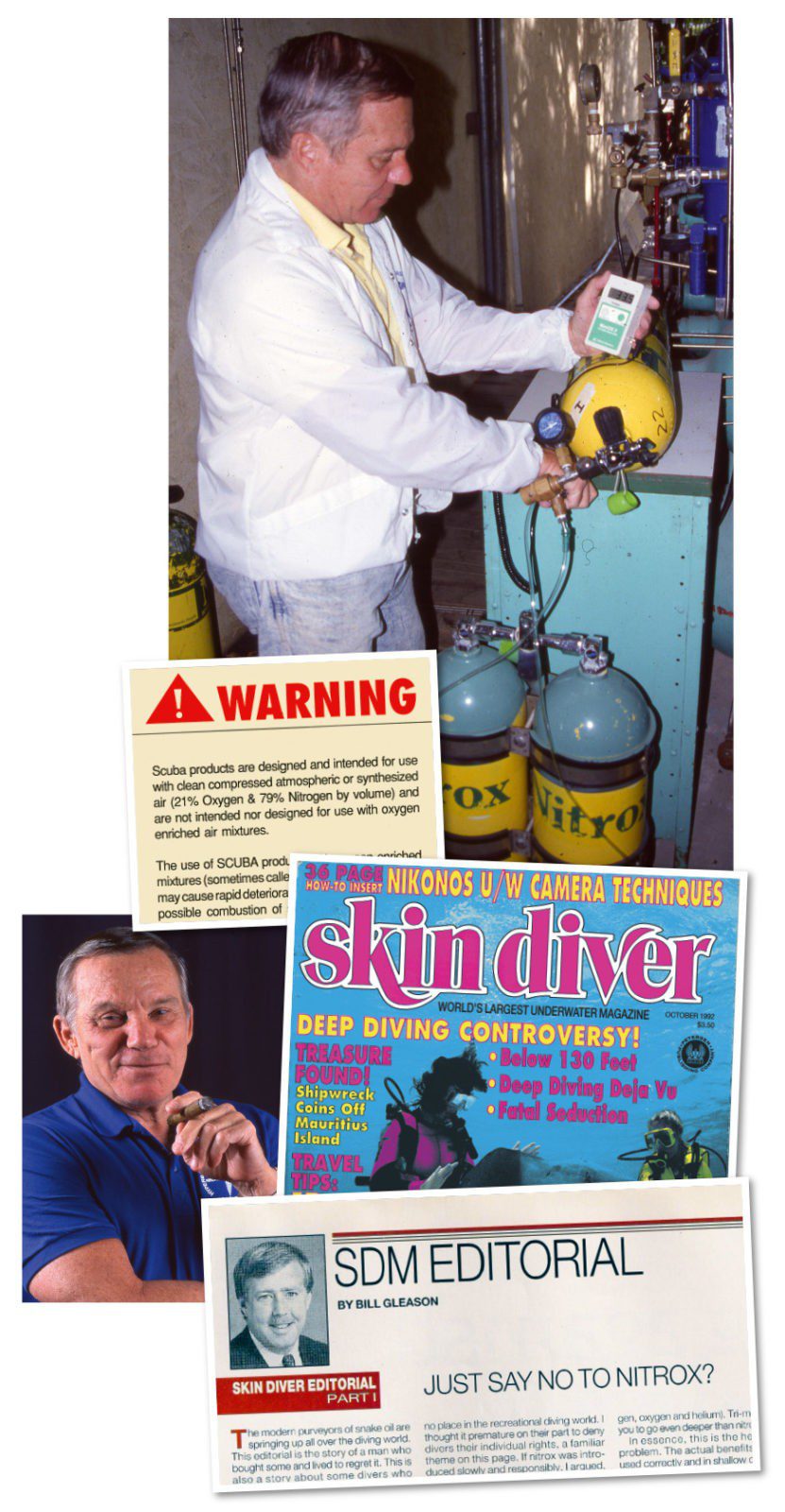

NOT SURPRISINGLY, there was dramatic pushback from the existing recreational-diving industry establishment, which had at the time little or no knowledge-base of nitrox or mixed-gas technology and was concerned about safety, blending methods and the potential for oxygen fires.

In the autumn of 1991, Bob Gray, DEMA founder and executive director, decided to ban nitrox vendors and training agencies such as IAND and ANDI from attending the annual international trade show.

I later learned that the move was instigated by the Cayman Water Sports Association, which was concerned about divers violating nitrox depth limits and also didn’t want tourist divers extending their bottom times, thank you very much. It also had the support of Skin Diver magazine – Cayman Water Sports was SDM’s largest advertiser at the time.

Many heated phone calls and faxes were exchanged. Tom Mount, who had become president of IAND and changed the name to the International Association of Nitrox & Technical Divers (IANTD), and Ed Betts, president and co-founder of ANDI, flew out to meet Gray.

While these talks were going on, I enlisted the help of Dr Bill and, along with Diving Unlimited Inc founder and CEO Dick Long with his Scuba Diving Resources Group and Richard Nordstrom, then CEO of Stone’s company Cis-Lunar Development Labs, organised the Enriched Air Nitrox (EAN) Workshop in January 1992 in Houston, Texas.

The workshop took place days before the DEMA show was to be held there.

Our goal was to bring all the stakeholders together to discuss nitrox and its uses. In light of the workshop, Gray agreed to rescind the ban on nitrox vendors attending DEMA.

As a result of the workshop, too, the sport-diving community established the first set of policies addressing the use of nitrox, as well as establishing that nitrox was not limited to technical diving but could be used by all sport divers.

We issued the findings from the workshop written by Dr Bill in technicalDiver Vol. 3.1 that July.

That year, the first page of the DEMA exhibitor’s guide offered a warning about using nitrox with scuba equipment. Ironically, it generated an enormous buzz at the show, causing attendees to ask: “What is nitrox?” This proved to be great advertising for mixed-gas technology and the training agencies.

THE SUMMER OF 1992 was a tragic one for the fledging tech-diving community. There were eight high-profile diving fatalities, including two on the Andrea Doria wreck and one at the Ginnie Springs cave system in Florida, along with a number of close calls that resulted in injury.

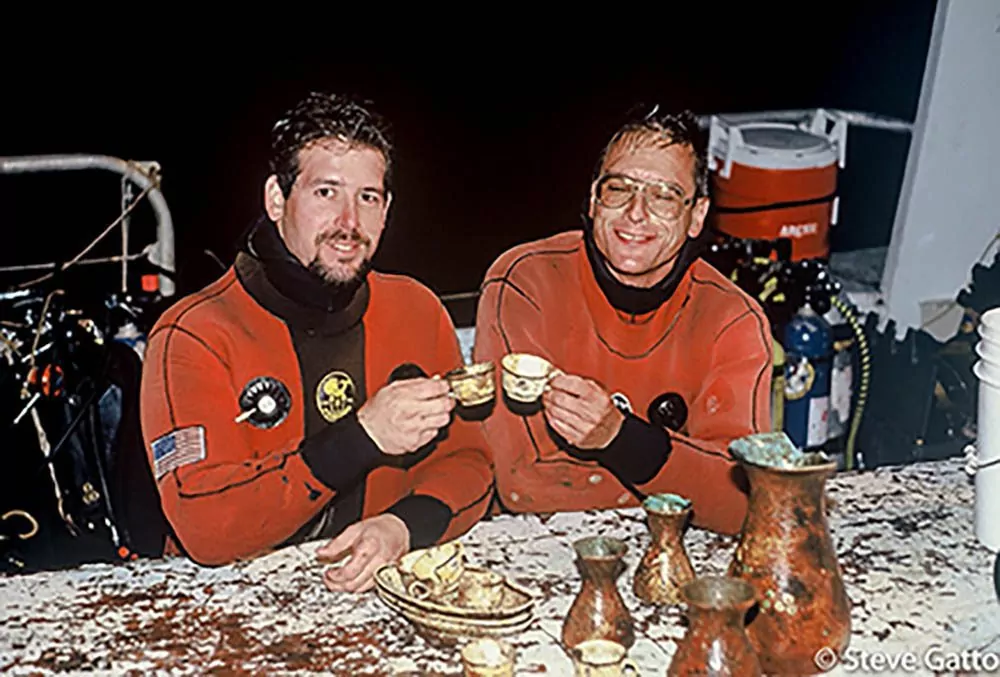

Then that autumn there was a double fatality involving a father-and-son team on the unidentified German submarine, referred to as the U-Who (later identified as U869 by John Chatterton and Richie Kohler).

Many feared that these deaths would bring on government regulation and effectively shut down technical diving.

With a rising number of fatalities, Skin Diver magazine went on a crusade with a three-part editorial series in the last three months of 1992, calling for an end to deep diving and nitrox use, or at least a return to the closet.

Editor Bill Gleason in his October 1992 editorial Deep Diving / Nitrox Perspective, wrote: “Get back in the closet and give responsible divers the opportunity to close and lock the door on deep diving.”

The fact that some of these editorials confused the use of nitrox with deep diving shows the lack of information and understanding at the time regarding the technology. Nitrox is typically used as a bottom gas on relatively shallow dives (less than 40m), and by technical divers as a decompression gas following deep helium dives.

Meanwhile, the Cayman Water Sports Association issued a warning that the local chambers would not treat divers who had been bent while diving nitrox. Famed Skin Diver columnist ER Cross even took a stand with a column entitled Why I Won’t Use Nitrox.

Of course, at that point it was too late to put the genie back in the bottle.

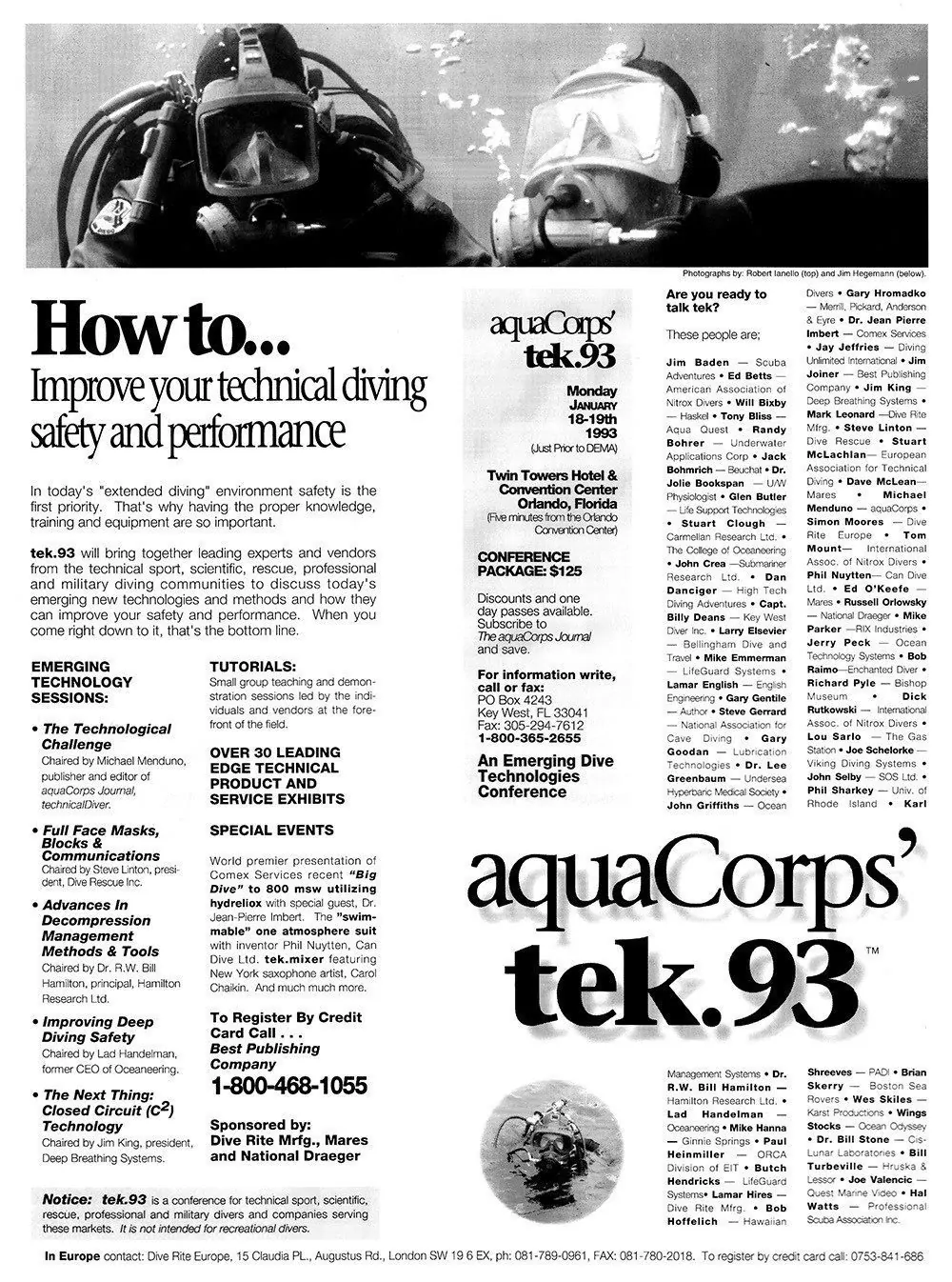

In January 1993, aquaCorps held the first annual tech-diving conference, tek.93, in Orlando, Florida, again just before the DEMA show.

This brought together members of the technical, recreational, military and commercial diving communities for the purposes of education and information-sharing, as well as addressing the recent spate of diving accidents, and what was needed for the technical-diving community to move forward.

As a result of the conference a group of us including Billy Deans, Kevin Gurr and others put together the first set of community consensus standards or “best practices” for technical diving.

We published this as Blueprint for Survival 2.0 that June in aquaCorpsm #6 Computing. It was a set of 21 recommendations to improve technical-diving safety in the areas of training, gas-supply, gas-mix, decompression, equipment and operations, based on Sheck Exley’s original work on accident analysis Basic Cave Diving: A Blueprint for Survival.

In that book, Exley developed a set of 10 principles or recommendations based on thorough analysis of cave-diving accidents, and it had helped to reduce cave-diving fatalities.

We also kicked off a new section in the magazine, Incident Reports, which featured detailed analyses of tech-diving accidents and soon became one of the best-read sections of the magazine.

One of my favourite quotes at the time came from a scientific paper by Jean-Pierre Imbert, who worked on COMEX SA’s experimental hydrogen-diving programme and later became an IANTD tech instructor, and others: “Safety is the key consideration in diving. It entirely controls depth and time capabilities.”

Ironically the paper was entitled Safe Deep Sea Diving to 1500 Feet Using Hydrogen. It’s likely that few people at the time would consider diving to 457m or using hydrogen breathing mixes to be safe. But that was the lesson we were learning. Safety was everything!

Over the next few years the various tech training agencies, including the Technical Diving International (TDI) formed in 1994 by Bret Gilliam and Mitch Skaggs, and later Global Underwater Explorers (GUE), started in 1998 by Jarrod Jablonski, developed solid training courses and the safety record improved.

Technical diving began to establish itself as a legitimate branch of sport diving, and mix technology in the form

of nitrox was gradually adopted by the recreational side of the diving business.

By 1995 PADI, along with the British Sub-Aqua Club (BSAC), National Academy of Scuba Educators (NASE) and Scuba Schools of America (SSA), joined other recreational and technical diving training agencies to offer enriched air nitrox training. The era of single-mix technology – air-diving – was dead.

The establishment of tech diving and nitrox use helped fuel the development of what one might call a mixed-gas infrastructure at the retail dive-store level. This was a necessary step for the eventual emergence of rebreather technology.

Read parts 1 and 3 here: