DIVING NEWS

Solved: the ‘stinging water’ riddle

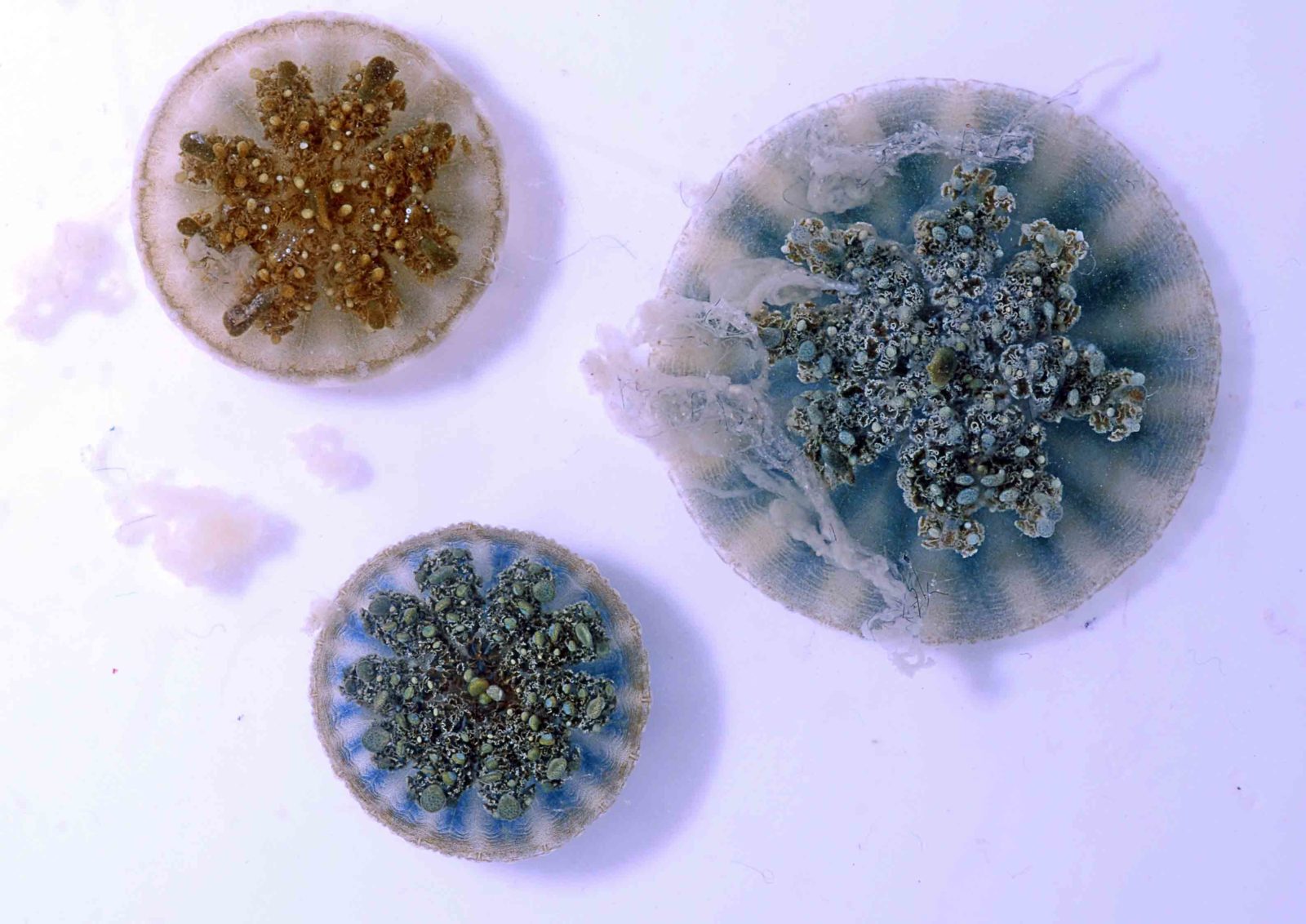

Cassiopea jellyfish releasing mucus.

The mystery of how the “upside-down jellyfish” Cassiopea xamachana, which has no tentacles, manages to sting swimmers without touching them has been solved.

The species is commonly found in sheltered waters such as lagoons and mangrove forests, and water-users with uncovered skin in their vicinity have suffered from what has long been described as “stinging water”.

Now a scientific team from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Nautical History, the University of Kansas and the US Naval Research Laboratory have pinned the cause on gyrating balls of stinging cells fired from the jellyfish, and have given them the name “cassiosomes”.

“This discovery was both a surprise and a long-awaited resolution to the mystery of stinging water,” said Cheryl Ames, museum research associate and associate professor at Japan’s Tohoku University.

She, National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) zoologist Allen Collins, and colleagues, had become curious about the phenomenon after experiencing it themselves in the course of their research.

They had not been sure whether their stinging, itching skin could be blamed on jellyfish, on severed tentacles of other jellyfish species, sea-lice or anemones, but observing Cassiopea collected from Bonaire in museum laboratory tanks revealed that when agitated or feeding they released clouds of mucus.

Under the microscope, the scientists were surprised to see “bumpy little balls” spinning and circulating in the mucus. More sophisticated imaging indicated that these were spheres of hollow cells.

Most of the outer cells were nematocytes or stingers, while others had cilia, filaments that served to propel the cassiosomes. In the jelly-filled centre of each sphere was a piece of ochre-coloured symbiotic algae of the same sort that lives inside the jellyfish.

The team detected cassiosomes clustered into spoon-like structures on the arms of the jellyfish and found that, when provoked, thousands of them would slowly break away, mingling with the jellyfish mucus as they went. Three different toxins were detected in the mucus.

17 February 2020

Photosynthetic algae that live inside Cassiopea jellyfish supply most of their nutrition, but it is now thought that when photosynthesis slows they supplement their diet using the toxic mucus, which incapacitates prey and keeps it close by. The cassiosomes turned out to be efficient killers of brine shrimp in the laboratory tank.

“They’re not the most venomous critters, but there is a human health impact,” said Collins of upside-down jellyfish. “We knew that the water gets stingy, but no one had spent the time to figure out exactly how it happens.”

The team have now identified cassiosomes in four closely related jellyfish species and are keen to examine more.

Their open-access study has just been published in Nature Communications Biology.