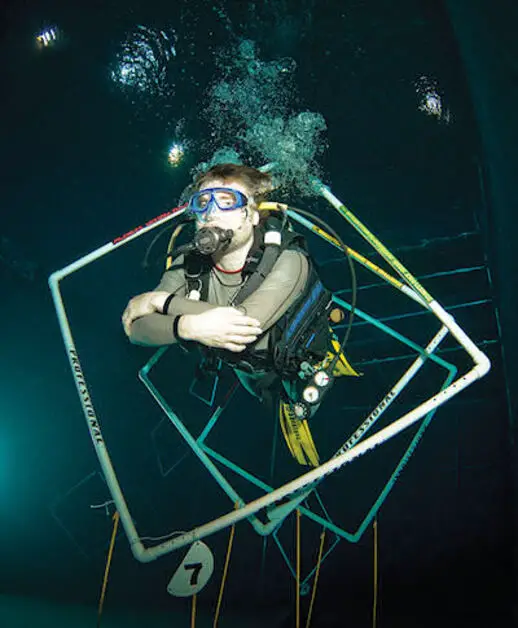

How good is your buoyancy control? The recent DIVER Buoyancy Challenge at Action Underwater Studios saw 60 divers find out more about their skills.

Sean Eaton, Andrew Pugsley and Steve Warren analyze the weekend, and look at why buoyancy control is so important.

The DIVER BUOYANCY CHALLENGE, created by Mavericks Diving and DIVER, consisted of a series of assessable tests designed to replicate diving situations in which buoyancy control could affect safety or the underwater environment.

The event took place over a weekend in March, and the secondary benefit was the social element.

Participants, many in club groups, gathered in the cafe/bar at the Action Underwater Studios in Basildon, Essex, which was hosting the event.

The studio was ideally suited with its 6m-deep filming tank, and the divers could learn more about the underwater special effects used in the movies made there by talking to directors Fred Woodcock and Geoff Smith.

Fifty-eight divers of all experience levels turned up to test their abilities, to learn about themselves and to compete for 10 prizes.

They ranged from a PADI SEAL (pre-certification youth) to instructor-trainers and technical divers.

Would the instructors and divemasters walk away with all the prizes? Should a handicap scoring system have been used? Clearly not!

This was an objective test, with no special treatment for anyone, so the results are revealing and the prizes well-deserved.

The challenge was designed by Mavericks Diving instructors Steve Warren and Andrew (AJ) Pugsley.

They specialise in continuation training – in particular, buoyancy-control workshops and underwater photography.

Their personal diving interests, wildlife (particularly sharks) and photography, have driven home the importance of instinctive buoyancy control to ensure their own safety, and for close animal interactions.

Steve and AJ stayed in the water as guides and safety cover. Participants were briefed on the surface before being led to each obstacle in turn.

Through the use of underwater flashcards, they could concentrate on the task without having to worry about where they were supposed to be.

Two participants at a time were put through the obstacle course, completing the same tests but in a different order.

The course took around 10 minutes, but was not assessed on time taken. Steve and AJ did not score or judge, but ensured that the rules were followed on each test.

THE JUDGES OBSERVED from outside the tank, through the two filming windows.

They were Mike Harwood (former Health & Safety Executive inspector and an expert in diver safety), and Paul Biggins and Jon Bramley (Seasearch tutors representing the Marine Conservation Society, and concerned about protecting the marine environment from the effects of poor diver buoyancy).

The judges gave participants penalty points when contact was made with a frame, a skittle was displaced, or an ascent time was out by a 5sec block.

Each diver was weighed in the water to determine his or her over-weighting. At the start of the dive, most should be 2-3kg negative to compensate for weight of air that will be lost from the cylinder.

At the end of the underwater obstacle course (described in the panel above), a weight-ditching exercise was conducted.

Divers started with their hands on their head, then had to ditch their weights and return hands to head. They were timed to see whether the process would be fast and instinctive.

The inspiration for this test was the statistic that in 85% of fatal recreational diving accidents the weights are still in place when the diver is removed from the water (Caruso, 2004).

Finally, participants underwent a theory quiz in which some of the questions were of the type found in certification exams, and some more challenging, encouraging divers to think deeply about buoyancy-related issues.

The results of the weighing, weight-ditching and theory quiz were not used in the final scores on which the prize-giving was based.

HOW DID THEY DO?

The age range of participants was 12-74, the mean age 37. The experience range was 7-1000-plus dives, with the mean at 296 dives. 71% of entrants were PADI divers, 21% BSAC and the remainder GUE or TDI.

The best score was 3 and the worst 65, with one diver not being allowed to complete the exercises due to destruction of each station! The average score was around 20.

Of the top 10, six were leadership-level divers, one was a technical diver and one a PADI SEAL (formally uncertified).

The results histogram showed a fairly noisy distribution, to be expected of a small sample size, although it seemed to start to resemble a normal distribution.

This indicated that the difficulty level of the test was fairly appropriate to the sample group.

Defining an acceptable buoyancy-control standard based on these data would be highly subjective – it should arguably be adjusted to specific diving environments.

It is interesting, however, to compare the relative scores of leadership-level divers (divemaster and instructors) to the rest.

59% of non-leadership level divers scored better (lower) than the average, while the scores of 61% of leadership-level divers were above average.

This suggests that the buoyancy control of divemasters and instructors is no better than that of other divers.

This could be interpreted as the non-leadership level divers being fully trained and competent in terms of buoyancy control.

However, if you consider that the average score of 20 in a 10-minute session equates to kicking the reef or wreck 60-100 times during a typical dive, it might be argued that the standard itself is too low, and that more should be expected of divers once they reach divemaster or instructor level.

The test that gained divers the most penalty points was the 45sec ascent. On average each diver gained more than 4 points, and they were generally too slow.

The average diver took 1.5 times as long to complete the ascent as was specified.

A slower ascent might be considered safer, but remember, that extra time spent at depth will increase nitrogen uptake and decrease available air supply.

Most revealing from this test, however, was the observation (not scored) that many divers would be ascending, then find themselves dropping back down.

Many divers have been trained to kneel on the bottom and dump all the air from their BC before starting their ascent. This seems an unnecessary and sometimes impractical routine, which observations suggest leads to problems controlling ascent.

There were limitations to the methods used – scoring per contact made with a frame, for example. If a diver was permanently in contact with a frame, they would score only one penalty.

To overcome this, the scoring system gave an additional penalty point for every 5sec of contact.

Thinner divers might be said to have an advantage, because they have more room to move around within a frame before touching it.

This was not addressed, but it’s worth noting that the top 10 scores were fairly representative of a distribution of body sizes.

Divers were allowed to dive with any kit configuration with which they felt comfortable, as long as it was safe. There were twin-set divers with wing BCs, a single side-slung no-harness configuration, and everything from drysuits to swimming shorts.

WEIGHTING

The over-weighting test showed that the majority of divers were correctly weighted (2-3kg negative). However, some were at least 5kg overweighted (7-8kg negative).

Only six participants elected to conduct a weight check on site before the tests.

The weight-ditching exercise was completed typically in around 4sec, with some divers taking rather longer.

It is recognised that one reason for prolonged times could be that the exercise was insufficiently explained and understood.

Dropping quick-release weights should be a rapid process, and while there were a few fumbles, inability to release doesn’t appear to be the reason for people failing to ditch weights in an emergency.

It seems that divers simply don’t consider this option when they get into trouble.

Overall, the challenge helped divers to discover their strengths and weaknesses. Most were able to tell where they had dropped points, giving them an indication of areas for improvement.

“Buoyancy control is an essential skill, but after initial training, how often is it re-evaluated?” said judge Mike Harwood afterwards.

“The Buoyancy Challenge was more than a competition. It gave each entrant an opportunity to re-evaluate their buoyancy-control skills.

The various Diamond Reef System exercises certainly evaluated all the essential buoyancy-control skills in a fun way.

“This challenge was a win-win situation, as all entrants will have gone home with a better understanding of their strengths and weaknesses at this skill.”

We hope that everyone who took part in the Buoyancy Challenge enjoyed the experience, too.

WHY BUOYANCY CONTROL IS SO IMPORTANT

A DIVER LOSES HIS LIFE inside a wreck. Thirty metres down, a diver making a night rescue initiates a controlled buoyant lift, only to find his fins touching the seabed when he thought the two of them were ascending.

An entry-level diver gets to one of the last skills of his scuba course and finds that, after removing his 6kg weightbelt, he still sinks. An out-of-air diver on the surface drops beneath the surface and drowns.

A diving instructor plunges to 57m at breakneck speed, and is nearly overcome by narcosis.

A buddy-pair sharing air on a decompression stop lose their grip on each other – one falls back into 40m of water and is killed; the other embolises as he shoots to the surface.

Each of these real incidents occurred through a diver’s failure to understand and control buoyancy.

Instructors teach divers a range of skills at entry level, including preparing for hazards they will probably never face.

To cope with an out-of-air emergency, most divers learn controlled emergency swimming ascents and use of alternative air sources. But buoyancy control is a skill we use on every dive.

It’s one of the foundations of safe diving, and when it breaks down, it places us at risk. Do we give it the thought it deserves?

OVERWEIGHTING

Diving incidents often have their genesis far from open water, perhaps years before they even happen. Many that involve loss of buoyancy control are a result of overweighting.

Entry-level divers should have been taught how to make a formal buoyancy check. This is not something you can do once and forget, though instructors may fail to emphasise this fact early on.

Breathing is one major variable. Before that first pool session, new divers normally do a weight check. They are usually nervous, so breathing more deeply, which makes them unrealistically buoyant.

The instructor adds weight until the students sink, then may add more to keep them firmly on the bottom, and easier to control.

As the students relax, they breathe less deeply and need less weight. They are progressively becoming more overweighted.

If this isn’t explained and demonstrated through further buoyancy checks, and weight removed, they may accept being overweighted as normal.

After certification, they continue to dive this way. Even experienced divers often take deeper breaths at the start of a dive trip, and can drop weight as the holiday progresses.

Other variables affecting buoyancy, especially for travelling divers, are cylinder type, water salinity and suit thickness and construction.

Neoprene suits also wear out, becoming less buoyant as the foam breaks down. So buoyancy checks should be a regular part of our defensive diving practices.

Overweighting doesn’t need to be substantial to create big problems. For every kilo of excess weight, you need to displace a kilo of water to compensate, which means putting a litre of air into your BC or drysuit.

It doesn’t sound much, but at 10m divers using expanded neoprene suits will have lost half their buoyancy, so will have 2 unneeded litres of gas to control.

Think of a 2-litre Coke bottle full of air, and how fast that would fly upwards from 10m. Would you really want to be wearing it?

Each scuba dive involves a number of phases that call for different buoyancy-control skills sets.

Each presents hazards, which should be identified, anticipated and prevented or, at worst, coped with and survived.

DESCENT PHASE

This phase starts with divers being overweighted. This is inavoidable, because they are carrying a full tank of gas and its weight (about 1kg per 800 litres of air) has to be equalled with enough weight to ensure that they can remain submerged when most of it has been breathed.

Otherwise they may be unable to slow their ascent and hold a safety or stage deco stop.

During descent, several problems can occur. Middle-ear squeeze is a likely one.

Divers are taught that if an ear sticks descending, they should halt, rise a little and gently try to equalize. Properly weighted divers in control of their buoyancy can descend very slowly.

To make a fast descent they would need to fin hard, to get, for instance, into the lee of a Maldives reef against strong current. So if an ear sticks, they can halt the descent instantly.

Overweighted divers will sink quickly and, if their ears stick, are likely to continue dropping, with additional pain and damage.

Another problem is buddy separation, particularly in poor vis, when one diver sinks faster than the other.

A greater risk is a fast, uncontrolled descent into deep water, especially near walls.

Slight overweighting can easily double your initial descent rate, and this will continue to increase as you lose buoyancy through suit compression.

Fast descents can speed the onset and severity of narcosis, put you into the oxygen-toxicity zone, especially if using nitrox, and place you into unplanned-for decompression obligations.

Even highly experienced and qualified divers have died during the descent phase after entering the water with their gas turned off, unable either to breathe or inflate BCs or drysuits to achieve positive buoyancy.

Even instructors have died when swept into the water with their air off.

It’s good practice to have your air on and BC inflated enough to provide sufficient buoyancy to keep your head above water whenever there’s a risk of falling in, such as when sitting kitted up on a RIB.

We would encourage divers always to check that their own air is turned on.

A risk of the “hands on” buddy check, where another diver checks that your air is on, is that he may turn it off and back half a turn.

Your pressure gauge will indicate that your air is on but, at depth, gas-flow could be dangerously restricted.

NEUTRAL PHASE

While swimming around, you will normally want to be neutrally buoyant and neutrally trimmed. Divers who lack good buoyancy skills have to work hard, and so burn far more gas than a buoyancy-savvy buddy.

Overweighted divers are often seen kicking furiously, and doggie-paddling. They are sinking, fighting to stay in midwater.

Gas consumption increases dramatically and, on diving holidays, when everyone may have the same-size tank, they are the most likely to have to surface first.

No sensible diver plays the air game, proclaiming either that they use less gas than anyone else or trying to match those who do.

However, there’s no denying that using far more air than your buddies can cause embarrassment.

Neutral buoyancy helps solve this problem by reducing effort. But simply pumping air into your buoyancy controller, or BC, isn’t the best way.

THE AVERAGE ADULT’S LUNGS can hold about 6 liters of gas, so a full breath provides 6kg of lift or buoyancy. Coincidentally, that’s roughly how much buoyancy many coldwater wetsuits provide.

About 1.5 liters of gas always remain in the lungs to keep them from collapsing.

That leaves 4.5 liters that we can move in and out at will; so we can adjust our buoyancy by as much as 4.5kg, or around 20% of the capacity of a modern recreational BC.

Early aqualung divers used their lungs as BCs, but the thicker your suit and the deeper the dive, the greater the loss of buoyancy and the harder it is to remain neutrally buoyant by using your lungs alone.

Eventually it becomes impossible.

The more you overweight, the harder you have to work to control the air in your BC. Each depth change requires that you admit or release air.

Gas expansion and contraction ratios are greatest in the shallows, so buoyancy control is hardest here for overweighted divers.

Neutral trim is an important part of easy diving. Water is 800 times denser than air, and pushing through it is very hard work. To double speed through water takes four times more energy.

Being neutrally buoyant means that you can float effortlessly and minimize gas use, but if you aren’t streamlined, swimming is inefficient and tiring.

Working hard and overbreathing under water creates a lot of potential problems. The obvious one is that gas consumption goes up and dive-time goes down, but there are other physiological disadvantages.

Breathing hard increases your inert gas loading. Divers are taught that if they work hard under water, the risk of decompression illness increases.

Dive times should be shortened, or safety and deco stops extended, to reduce this, but how often is this considered?

Carbon dioxide retention is also a problem of overbreathing and this tends to exacerbate the effects of narcosis.

Streamlining isn’t helped by overweighting. With most weight worn on the waist, your body is naturally pitched feet-down, head-up.

More weight increases this tilt. Air in the BC rises to inflate the area behind the shoulders. The incline of your body and air gathered in the BC creates drag.

Reducing weight reduces the amount of air needed to compensate and, in turn, minimises drag from the BC.

What air is in the BC should ideally sit in the channels beside the tank and help stabilize you, preventing you rolling while swimming, and keeping you horizontal so that you cut through the water with minimum effort.

DURING THE NEUTRAL PHASE, divers also need to retain their spatial awareness, a thought process that works only if you have good buoyancy skills or can recognize their shortcomings.

It protects you and the environment.

Overhead environments such as caves and shipwrecks typically have excellent visibility, as the water is often still, but divers untrained in the correct finning techniques may kick up silt, turning visibility from clear to zero in an instant.

Close to the exit but unable to see it, divers can simply run out of air.

Poor spatial awareness also hurts the environment. Fin-tips lack nerve endings, and coral is an easy victim of the misplaced fin-kick.

Skilled divers are very aware of where their fins are in relation to their surroundings, and also where the thrust from the fin is going.

Using frog kicks, or using your lower fin to block the thrust from your upper fin, are useful techniques in overheads, when swimming over easily disturbed seabeds or near coral, to maintain vis and reduce damage to your surroundings.

Neutral trim and spatial awareness can be learned and practiced using obstacle courses such as Buoyancy Training Systems’ Diamond Reef program.

Practice makes you better – but there’s no shame in realizing that you need to improve, or are having a bad day.

Staying a little further away from vulnerable coral gives you room to manoeuvre and recover control if things go awry.

The best divers weren’t created in a blinding light and presented with their C-cards by God. They evolved, making a lot of mistakes along the way.

ASCENT PHASE

The way we ascend has changed. Ascent rates are around half of what they used to be, and direct ascents are a thing of the past.

Safety stops are the convention, and stage-decompression dives among sport divers are commonplace.

Both over- and underweighting contribute to problems associated with ascents. Overweighting leads to over-inflation of BCs and drysuits.

As divers try to control their ascent rate, a stop-go pattern can develop. Speed increases, they over-dump, become negatively buoyant and begin to redescend.

They then hit the inflator to get the ascent back underway, over-compensate again and speed up. It’s a vicious circle.

In shallower water, the situation becomes even harder to control. Buddy separations become likely, as the divers find it hard to maintain the same ascent speed and stay level with one another.

Air consumption is likely to increase when they are already low on gas, with the risk of running out.

Properly weighted, divers can ascend at a very slow rate. At their safety or deco-stop level, they can stop and make a free hang for as long as it takes.

Skilled divers use hang-time to practice midwater hovers, using computers for reference to maintain depth to an accuracy of 0.3m.

UNDERWEIGHTING CREATES other hazards. Underweighted divers in neoprene suits will become more buoyant near the surface, especially in the safety-stop zone.

There’s little they can do to stay under water unless there’s a convenient hand-hold nearby, an overweighted buddy who can keep them both under water, or a shot or anchorline to hang onto – with all its attendant risks.

Such divers become even more buoyant as they breathe down their tank. Divers have been bent through missing stops due to underweighting.

Ascents are usually routine, but some divers, usually in out-of-air situations, will be faced with emergency ascents, either for self-rescue or to assist others.

Divers equipped with an independent alternative air source, such as a pony, can handle an OOA situation within normal recreational depths and no-decompression limits with little drama.

But pony bottles are not routinely provided at resorts or on liveaboards.

Without one, problems quickly escalate. Sharing an alternative air source provided by another diver is the preferred next-best option.

During a shared ascent, divers need to maintain a firm grip on one another.

Ideally both should remain neutral, but if a diver is out of air he will not be able to inflate his BC or drysuit. So the assisting diver is likely to need to control buoyancy, to some extent, for both.

If the OOA diver is finning hard to maintain the ascent, gas consumption will increase several-fold, and if the rescuing diver is also low on air this increases the chance of him running out of breathing gas too.

The assisting diver must be buoyant enough to support a negatively buoyant casualty. If the divers then lose their grip, the assisting diver will ascend and the OOA casualty sink.

Overweighting simply increases the differential and the speed at which they separate. Similar issues arise with unresponsive casualties.

SELF-RESCUE TECHNIQUES involve Controlled Emergency Swimming Ascents and buoyant ascents.

CESAs are taught by most major training agencies. OOA divers retain their weights and make for the surface, attempting to exhale all the way.

Air in the drysuit or BC is dumped progressively in an attempt to remain neutrally or slightly positively buoyant.

Some agencies now require that divers ditch weight-systems as they reach the surface. This is good practice. Casualties have been seen to surface successfully, only then to sink back and drown.

Remember that when we do a buoyancy check, we aim to float at eye-level with a neutral lung volume. Our mouth and nose are below water level.

Panicking divers tend to want to keep as much of their body clear of the water as possible, and the head weighs about 5kg.

Supporting this above the waterline by finning while negatively buoyant is very tiring, and can become impossible.

All of which, and more, underlines why good buoyancy control should never be taken for granted.

The DIVER Buoyancy Challenge may be for fun, but its underlying intention is deadly serious.

THE TEST CIRCUIT

The obstacle course was largely based around the Diamond Reef system, which uses a series of plastic diamond-shaped frames as a reference point for buoyancy-control training and assessment.

The assessed part of the challenge consisted of eight underwater tests:

.1 DESCEND AND HOVER FOR 1 MINUTE

A frame was set up at 4.5m, the object to position one’s body in the center and hover without touching the frame, simulating a deco or safety stop. The safety divers measured the minute.

2. HIGH-LOW-MID-DEPTH TUNNEL

Three diamonds were arranged at different depths to form an undulating tunnel, simulating swimming through a cave, wreck or over a reef.

3. SKITTLE BOX

Four skittles were placed at the corners of a square. The diver descends into the square, lies on the bottom, then rises – all without displacing skittles by contact or fin-wash. This simulates dropping into a confined space, as when taking a photo.

4. KID’S PUZZLE

While holding position in the same frame as the 1min hover, the divers had to complete a suspended puzzle.

This task involves inserting a plastic shape from a bag in the matching hole in a box and is suitable for 3 months and up – easy! It introduces task-loading and simulates taking a photo or manipulating equipment such as a delayed SMB midwater.

Using a toy overcomes the fact that some divers may be more familiar than others with certain types of equipment.

The slightly buoyant toy was suspended by a lightly weighted line just below the centre of the frame, such that it couldn’t be used as a handhold.

5. SWIM-THROUGH TUNNEL

Three diamonds formed a tunnel of constant depth to simulate swimming through a cave, wreck or along a reef.

6. WEIGHTED GOODY BAG THROUGH TUNNEL

A goody bag had to be carried through the constant-depth tunnel to simulate the buoyancy effects of picking something up, such as a camera or artefact. It contained 4kg of weight.

7. REEL THROUGH TUNNEL

A line had to be paid out while swimming through the constant-depth tunnel. This simulates line-laying in a wreck or cave, or for a search pattern in open water, and increases task-loading.

8. 45-SECOND ASCENT

Ascend to the surface from the 6m bottom without using instruments. This tests time-appreciation and simulates loss or failure of a dive computer.

THE TOP 10

1st PRIZE

PRIZE FUJI DIGITAL CAMERA & HOUSING, FROM FUJI

GUE UK technical diver and PADI instructor Gareth Burrows from East Sussex flew the flag for DIR (“Doing It Right”) divers everywhere. He used a twin-set on his winning circuit.

“GUE courses are very heavily task-loaded, so it was just what I expected,” said Gareth. The high-low-mid-depth tunnel he considered the most challenging test, “as the hoops were so closely spaced. But we’re taught to be able to hold and stop whatever happens, so that was easy enough.”

The Challenge “was useful and will have opened a lot of people’s eyes,” said Gareth. “They teach what looks like a good buoyancy course here, and any practice is well worth doing.”

2nd PRIZE

PRIZE SEAQUEST PRO PEARL BC, FROM MAVERICKS DIVING

3rd PRIZE

INON FISHEYE LENS, FROM OCEAN OPTICS

Howard Ryan, of Bedford Scuba Divers BSAC, has dived only since 2007 and was just starting on his Dive Leader training.

“I think it’s a brilliant idea, because the whole buoyancy thing is under-rated,” he said. “We start with the skills, and only right at the end of training look at buoyancy, but it should be the other way around. To see some people trampolining around on holiday dives is horrifying.”

“I had no preconceptions, but I thought I’d enjoy the day. The kiddie’s toy was the hardest bit – I would forget all about the hovering.”

4th PRIZE

PRIZE MARINE BIOLOGY DAY, FROM JAMIE WATTS

5th PRIZE

PERSONAL U/W PHOTOGRAPHY DAY, FROM MARTIN EDGE

Geoff Eaton, a PADI Master Scuba Diver Trainer with the Sublime Diving Academy, Colchester, felt the Challenge would be more beneficial for Advanced Open Water Divers than OWDs.

“Open Water Divers are still getting to grips with their equipment,” he said. “My biggest problem is Open Water students coming up too quickly, so a good skill is learning to slow down.”

“I’d love to put a Rescue Diver group through this sort of course, as it’s designed to raise awareness. As a skill-set it’s superb, and it’s also a fun activity.”

6th PRIZE

SHARK AWARENESS DAY, BLUE PLANET AQUARIUM

David Pilgrim has been diving for nine years and is a PADI Staff Instructor in Manchester.

“To be honest I was just expecting a few hoops, but not to do some of the other things like hovering in the skittle space – which wasn’t so good without booties on.

“This pool’s great, and it would be really good to do something like this for our own students. You could use ideas like this in a drysuit training session, where it would be a bit easier with the air right across your back, and extend it to wreck penetration.”

“Something like this adds a new dimension to training.”

7th PRIZE

MARINE BIOLOGY DAY, FROM JAMIE WATTS

“A fantastic idea,” was the conclusion of Staff Instructor Debby Richardson, who had used the 6m Underwater Studio pool before and considered it to be “really good for buoyancy training”.

Had she found the Buoyancy Challenge circuit at all tricky?

“Well, yes and no. Although I do this sort of thing all the time, it’s surprising how much we were given to think about on this circuit.”

“There was one shape in that puzzle I just couldn’t get in, then luckily I had a good run.”

“I think the more divers get the chance to do this sort of thing, the better.”

8th PRIZE

INON U/W PHOTOGRAPHY DAY, UNDERWATER STUDIOS

Ian Palmer, an Assistant Instructor from Basildon, turned up at the Buoyancy Challenge with a group from Essex School of Diving.

“I knew there were wave machines here and I was expecting a heavy-duty current,” he said. In fact there was only a slight current generated on the day, in the area near the puzzle.

“That puzzle was the hardest test, and I also think I over-compensated when I found that there was weight in the goodie bag.”

“I’d do it again, and without a shadow of doubt I’d say that an exercise like this would be useful for trainees before they do their Open Water.”

9th PRIZE

INON U/W PHOTOGRAPHY DAY, UNDERWATER STUDIOS

The Leopold family achieved a remarkable three prize places. Simone Leopold was the runner-up, husband Stephen came fourth and their 15-year-old son Elliot, who had done fewer than 40 dives, came ninth.

“It was really good fun,” was the verdict of Simone, a BSAC Advanced Diver who has been diving for 25 years. “We would definitely bring people from our club to do something like this if it was a regular event, because buoyancy control is so important.”

She and Stephen both found the shape box the toughest challenge: “You got so focused on the puzzle itself. Taking the reel through the diamonds was interesting, too, and settling between the skittles makes you aware of the turbulence your fins can create.”

Stephen, a BSAC 2nd Class diver from the school of ’81, added: “This is an ideal training aid. In a normal diving situation people do tend to want to be overweighted, and so use more air.”

Elliot is an Ocean Diver of two years’ experience. “It was very good fun, interesting and a bit harder than I expected, especially the diamonds at different levels.”

The Leopolds liked the idea of organising a circuit of buoyancy tasks in their own club pool. “It would be simple to set up but could be quite challenging,” said Elliot

10th PRIZE

MARINE BIOLOGY DAY, FROM JAMIE WATTS

Lauren Noakes, like Stephen Leopold, is just 15, but unlike him she had not yet got beyond diving in a 2m-deep pool – the Rainham girl was a PADI SEAL.

“I’m halfway though my Open Water course, and I was expecting the Challenge to be really confusing – but in fact it was really good,” she told us after successfully completing the course, although she added that “hovering through the diamonds was quite hard”.

Clearly a natural diver!