How have mantas developed so many clever ways of feeding their faces, in particular the strategies that rely on close co-operation, and how do they decide which to use when? In the Maldives, where the world’s largest aggregation of reef mantas is found, researchers like HANNAH MOLONEY of the University of the Sunshine Coast, principal collaborator at the Manta Trust, are freediving to find out more

Unless you’re an avid storm-chaser, there are few cyclones in which you would willingly choose to immerse yourself. If you’re an ocean enthusiast, however, there is a “cyclone season” in the Maldives that not many people know about!

During the south-west monsoon, an unsuspecting reef inlet plays host to the world’s largest aggregation of reef manta rays. Hanifaru Bay becomes a melting pot in which large megafauna (including whale sharks) feast on the tiny nutrient-rich food called zooplankton.

When the water is a zooplankton soup, chain-feeding manta rays loop around, with the lead animal joining the trailing manta to create a large circle. As more mantas join the feeding the column builds, creating a vortex of water and plankton. This is called cyclone feeding.

A cyclone can begin at the water’s surface and reach all the way to the seabed, often presenting a 20m-diameter display of vortexing mantas.

Cyclone feeding is a rare feeding strategy that has only ever been witnessed in Fiji and the Maldives, yet it is relatively common in the Hanifaru Bay Marine Protected Area (MPA) in Baa Atoll. It is a foraging behaviour that is co-ordinated by a group of manta rays.

The cycloning mantas cause the water to move fast in an anti-clockwise direction, like a mini-eddy or current. This draws zooplankton into the pathway of these hungry feeding machines. The planktonic animals include crustaceans, copepods, worms, salps and eggs – some of the mantas’ favourite foods.

As a snorkeller observing this phenomenon from afar, it can sometimes feel as though you are being drawn inwards, just like a zooplankton, into the cyclone of mantas!

Giant face-spoons

Manta rays feed using their paddle-like cephalic fins, which act as giant face-spoons when unfurled for feeding. They race through the water at a targeted depth where the zooplankton is concentrated, using the propulsion from their wing-like pectoral fins.

Think 150 large individuals (some the size of a flat VW Beetle) with unfurled cephalic fins and mouths wide open, racing to scoop up as many speedy animals as they can, for the time that this ephemeral hotspot lasts.

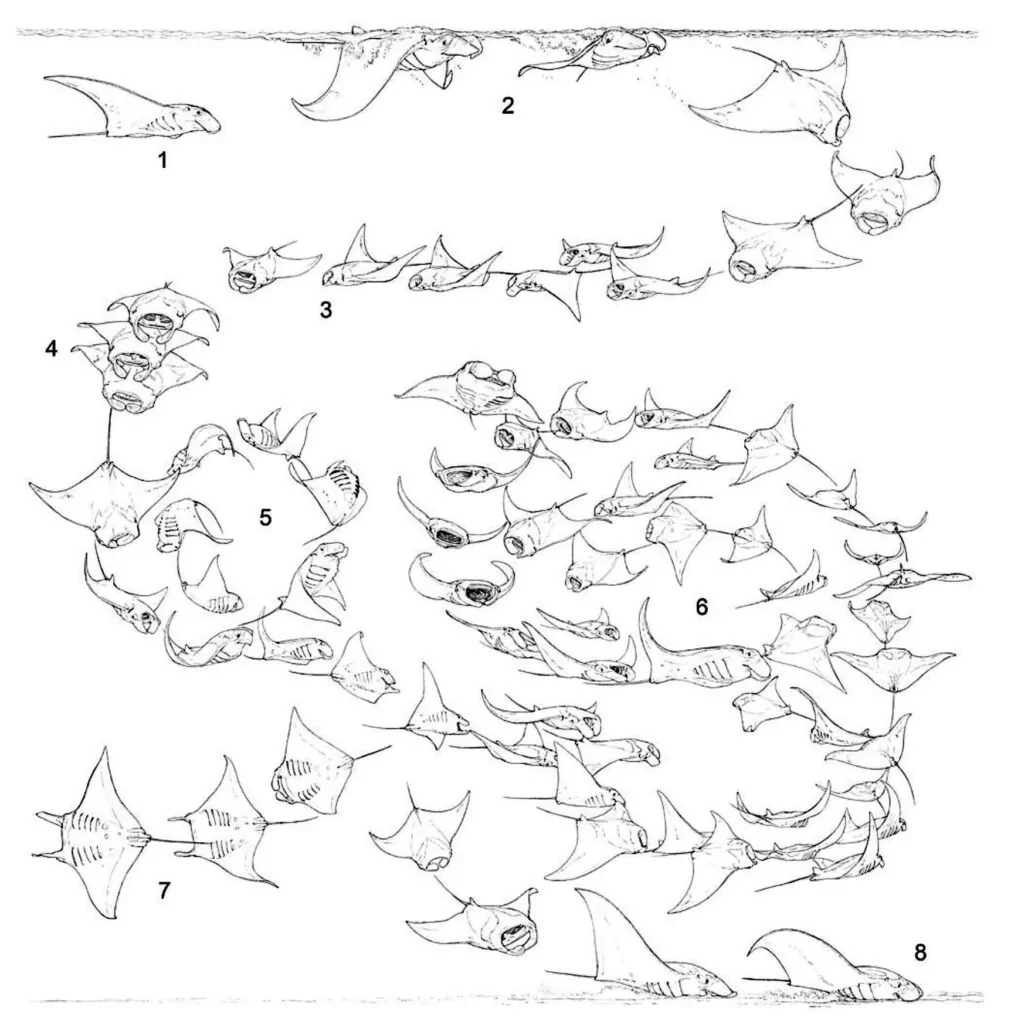

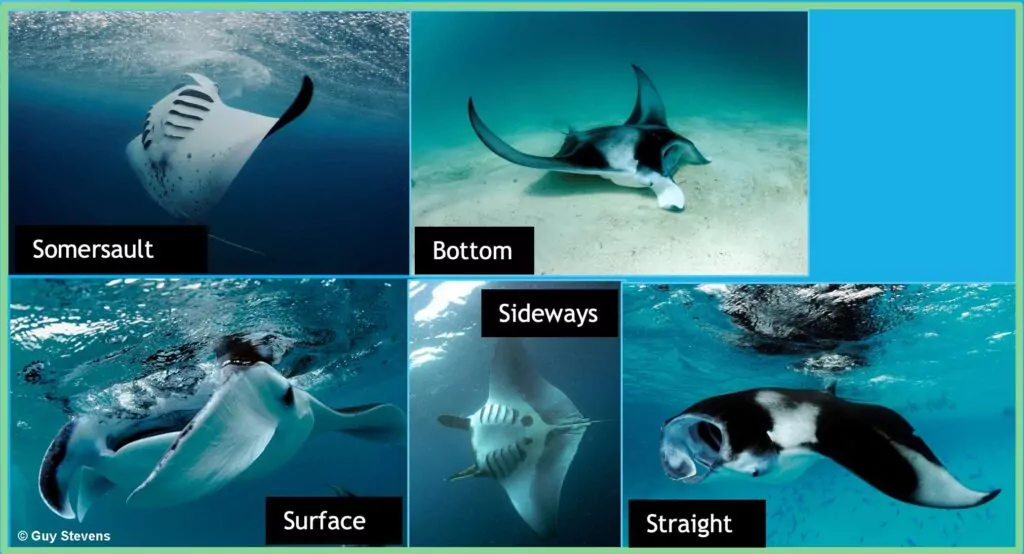

Manta behaviours are fascinating and complex, and we have yet to completely understand many of them, and the extent to which the rays can communicate. When we take a closer look exclusively at feeding behaviours, we can identify eight distinct foraging strategies, as defined in 2016 by Dr Guy Stevens, founder and CEO of the Manta Trust.

Some of these are “solo” strategies, for when manta rays feed alone (somersault, bottom, surface, sideways and, most common, straight feeding) and others are “group”, when the rays feed co-operatively (piggyback, chain and, of course, cyclone).

These strategies are employed to increase feeding efficiency, with varying benefits attained from each one. Because zooplankton and oceanographic conditions are never the same from day to day or hour to hour, mantas have adapted their foraging behaviours to account for varying types and densities of zooplankton and also various current dynamics / water movements.

The use of group strategies is believed to be linked to an increase in prey density. Mantas adopt co-ordinated or group feeding to improve their prey capture, enhance hydrodynamic efficiency and of course to avoid collisions.

If there wasn’t a rhythm or system to their feeding at a site like Hanifaru, mantas would spend more time dodging each other than feeding!

Research is currently underway by the Manta Trust and the University of the Sunshine Coast to further investigate what drives the behaviour selection while feeding, and why these mass aggregations of hundreds of mantas even happen.

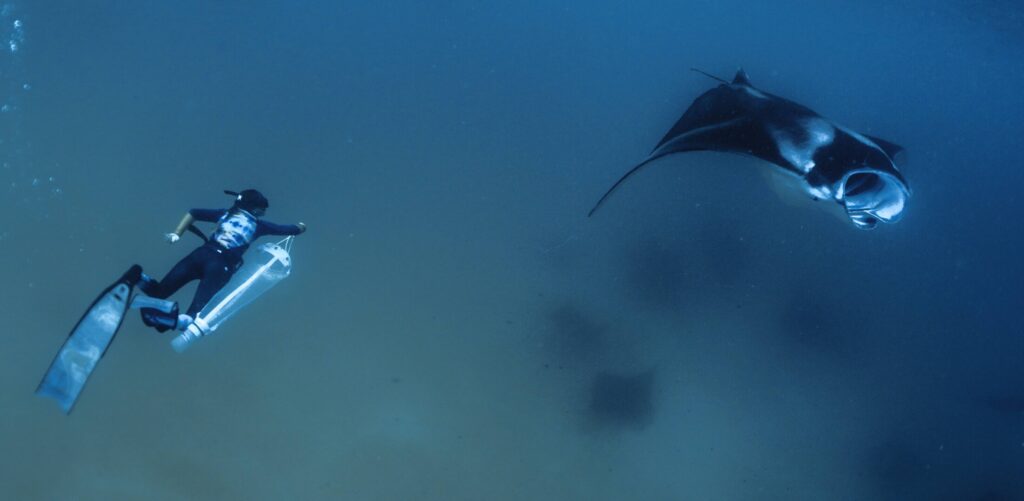

Over the past two years researchers have been collecting targeted zooplankton samples in Hanifaru Bay, but not in the “common” plankton-sampling way. Most plankton research is done by towing a net behind a boat, but because of the MPA status of this site there are many rules and regulations in place to mitigate the impact of tourism on the animals.

This means no boats, no scuba divers and a limited number of snorkellers at a time. The sampling has to take place using human power and on a single breath – by freediving.

Freediving challenges

This method allows researchers to take targeted samples at whichever depth the mantas are feeding, and to closely analyse the feeding strategies employed to scoop up their prey. However, freediving to 10m to tow a weighted net horizontally for 1 minute while narrowly avoiding close contact with hungry manta rays isn’t always a breeze!

This two-person job requires great attentiveness from the research assistant, who keeps a close eye on the surroundings, is on safety patrol, does fast-paced manta counts and records the various feeding behaviours.

In February 2023, researchers will be processing 100 feeding samples at the CSIRO plankton lab in Australia. With the dark cloud of climate change and the intensity of systems such as El Nino / La Nina looming over us, it’s more important than ever to study our oceans.

Climate scientists predict that zooplankton could decline by up to 50% in some tropical regions, affecting the availability of food for manta rays and other planktivores. This study will help us to understand manta-feeding ecology and behaviour, and also the drivers behind the world’s largest manta ray feeding site.

This research is important because food is important for survival – if we protect the small animals, the zooplankton, then large animals such as manta rays can continue to thrive.

This study is being conducted in collaboration with CSIRO Australia, University of Queensland, Plymouth University, Four Seasons Resorts and the Manta Trust.

Also on Divernet: 4 Manta Hotspots Identified In Philippines, Manta E-Gifts For Those Nightmare Recipients, Where To Find 22,300 Giant Mantas