There is always a palpable sense of excitement when speeding out to Lefteris Reef on a dive-boat. It is a place slow to give up its secrets, and one never knows what might be discovered.

Abundant marine life, ranging from soft corals to a resident moray eel, are certainties, but shards of ancient amphoras indicate that this is also a place rich in history. Not even breaking the surface, Lefteris has always been a notorious shipping hazard.

Also read: Unyielding pursuit: The finding of WW2 sub HMS Triumph

According to Greek historian Herodotus, at least three galleys hit the reef and sank during the failed second Persian invasion of Greece in 480 BC. King Xerxes then ordered a stone column built out of blocks weighing up to half a ton to be erected to prevent further loss.

Dating two and a half centuries earlier than the lighthouse of Alexandria, this beacon is the oldest navigational construction known in historical records.

In more contemporary times, Alexandros Papadiamantis (1851-1911), a celebrated Greek writer from Skiathos, mentions Lefteris Reef in The Poor Saint: “Lefteris releases cargos from its ships and frees sailors from the short burden of life.”

Despite its present wireframe lighthouse, Lefteris Reef has the distinction of having caused two more recent wrecks.

Built in 1956 and 58m in length, the cargo ship Vera ran aground there in 1999. At depths of 17 to 28m, the wreck now lies broken in two and remains easily accessible to divers of various abilities.

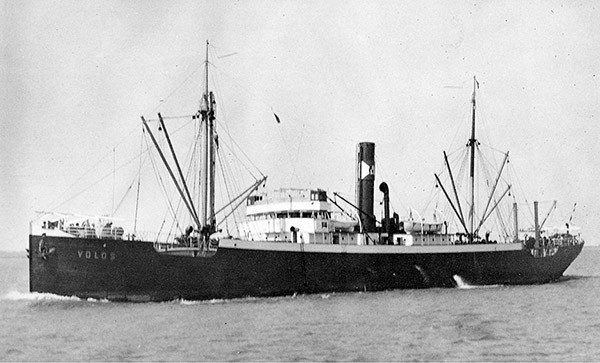

More intriguing is the ss Volos, an older wreck the identity of which was forgotten for almost 60 years. Its full backstory has only now been rediscovered.

The excitement of diving the Volos has a lot to do not just with the circumstances of its sinking (see panel) but with this backstory.

It is a deep dive that starts almost at the cusp of the recreational dive limit at more than 36m. Rolled over on its side, the ship’s remains are in two distinct sections, located just a few metres from each other.

The forward and deeper section is the foredeck and forecastle in its entirety. Frustratingly for non-technical divers, it lies on an incline, with the bow plunging down to 61m-plus.

As you descend past the two forward cargo-hold openings set in the steel framework of the ship, you can envisage Captain Pietsch peering out into the darkness from the bridge as the churning seas dumped sheets of water onto the foredeck on that fateful night.

You can imagine the helmsman trying desperately to steer the ship true and steady in a swell that periodically swallowed the forecastle whole, as she ploughed through crest and trough.

You can feel the panic when the First Officer alerted the Captain to the dangerous proximity of Lefteris, and conceive the horror as they realised that nothing could be done to avoid the inevitable. PENETRATING THIS SECTION of the wreck is easy, thanks to the open ribbed framing. As you delve into the hull, there are no wide-open cargo spaces, as you might expect, only a forest of slowly decaying steel beams and columns adorned with coral.

At one time, this area would have been packed with munitions for the Imperial German Army. Now, with its complex steel structure silhouetted against the deep blue of the Aegean, it is eerily empty.

The aft section, which lies at around 36m, is more of a mystery. In 1942, during the height of the Nazi occupation, Austrian marine biologist and pioneering underwater photographer Hans Hass was in Greece on a scientific expedition.

Using surface-supplied diving techniques and rebreathers (it would be another year before Jacques Cousteau co-invented the Aqualung) Hass actually filmed the Volos under water.

Miraculously, the footage can still be seen today, in the 1947 documentary Menschen Unter Haien (Men Among Sharks). It shows the wreck upright and fully intact in only 10-12m of water.

Seventy-five years later, the remaining aft section is only a small portion of what it should be. At roughly 10m long and with no conclusively identifiable features, it could be any part of the ship rear of the foredeck other than the distinctive poop and stern.

On approach, the first thing you notice is a lifeboat davit, laden with marine growth and drooping down towards the sand. However, this does not identify the aft section as being near the boat-deck.

Closer inspection reveals that the davit is resting on the outside of the port gunwale, meaning that it fell onto its present position.

Emanating from the gunwale are the cross-beams that used to support the deck, but these are now vertical and twisted. Many are broken and have become snags for unsuspecting fishermen.

Impossibly, the distance from gunwale to sand is only 3-4m. It is as though three-quarters of the ship’s 12.6m breadth is somehow buried deep in the sand – but this is just an illusion. Sadly, it is simply missing.

The post-WW2 ethos was to salvage old wrecks for scrap. Between 1945 and 1952, the Greek government demolished more than 350 wrecks for this reason.

Although ss Volos is not on any known official list, it was not excluded from this indignity. Its single propeller, the superstructure and most probably the highly prized engine and the boiler were all scavenged. Methods were often crude, with dynamite being employed, despite the environmental damage caused.

So the Volos, as it is today, is just a partial wreck, but what remains invites divers to explore some fascinating events in history – which also include one more irresistible twist to the tale.THE 1942 HANS HASS EXPEDITION included fellow-Austrian Alfons Hochhauser. Having lived as a shepherd and then a fisherman in the Pelion region for years before the war, he was fluent in Greek and thoroughly familiar with the Sporades and the surrounding maritime area.

In 1928 he was responsible for the recovery of the famed Artemision Bronze, a life-sized statue of Zeus (or perhaps Poseidon) made around 460 BC and now a prime exhibit at the National Archaeological Museum of Athens.

The statue was recovered from a (possibly Roman) shipwreck dated to around 250 BC off Cape Artemision in northern Evia – just 10 nautical miles south-west of Lefteris.

In entries made in 1942, Hochhauser (who was later to use his position in the Wehrmacht Secret Field Police to save Greeks – many of whom were his friends – from the draconian measures imposed by the Nazis) writes in his personal diary;

“July 14th – We are the ones who took them out of the sea and they were the ones who packed them in wooden crates and put them into the hold. I have counted 12 crates so far. All of them are full of amazing artefacts from the sunken city. Some of them are like new.”

“25 August – last day. Tomorrow we are coming back – ‘X’ [Hans Hass] is clearly happy – I paid my debt from the past. But I’m not happy at all. The movies we shot were very good, but the hold is full of crates. I consider how different it is now than 1928 when we discovered the ancient god.”

Although never rediscovered, the “sunken city” reportedly lies somewhere between Psathoura and Gioura islands, which are, needless to say, also in the Sporades. Given that Lefteris Reef has claimed so many wrecks over the years, logic dictates that if Hass and Hochhauser found any ancient artefacts while they were there to film, they would also have shipped them back to Nazi Germany.

It is more than likely that the shards of ancient amphoras that can still be seen today are a mere remnant of what once was. Or perhaps – as any good diver might assume – they are just the tantalising traces of what has yet to be discovered.

• Two local dive centres that organise dive trips to Lefteris Reef are: Skiathos Diving Centre, skiathosdiving.gr, and Zoumbo Sub, zoumbosub.gr. The author wishes to thank Yiannis Iliopoulos and Androniki Iliadou of Athos-Scuba Diving Centre, Halkidiki for their help with his article.

THE VOLOS

Laid down in 1902 by Neptun Aktiengesellschaft of Rostock, and originally called the Thasos, the vessel was assigned the unenviable role of munitions transport in the German Imperial Navy during World War One. Seriously damaged in 1917 after running aground near the northern Swedish town of Lulea, she was towed back to Germany after the war and repaired.

In 1921 she was relaunched as the Volos and started ploughing a regular route between Hamburg and Istanbul.

The Volos came to grief 10 years later at 8.14pm on 21 February, 1931, in heavy seas and force 8 to 10 winds, when she struck Lefteris Reef.

Captain Pietsch and First Officer Bohl both had acknowledged experience in Greek waters, but the ferocity of the storm and an unusually strong current got the better of them both.

Steering became ineffectual in a massive swell that eventually dumped the 86m steel vessel onto Lefteris as if she were a child’s toy, sending the three officers and 23 crew sprawling and putting their lives in grave danger.

With burst pipes and a cracked hull, Volos started taking in water. Desperate, Captain Pietsch ordered her full astern, but to no avail – the force of the impact had displaced both boiler and engine.

The radio operator commenced sending out an SOS, but unfortunately no one realised that the antenna had been short-circuited.

As the waves pounded the stricken vessel and the water continued to pour in, the generator finally failed and the ship was plunged into darkness.

Oil-lamps were lit but there was little the crew could do apart from shelter from the worst ravages of the storm and pray for salvation.

Against all reasonable expectation, navigation lights of a passing steamer were seen only two hours after the incident. The ship’s whistle was blown, but the steamer did not change direction and her lights agonisingly faded into the distance.

Incredibly, as the crew’s hopes seemed dashed, a second vessel was spotted. However, this also failed to notice the marooned survivors stuck on the reef in the midst of flurries of blinding spray and unforgiving seas.

Fortunately, the storm had abated enough to take them out of immediate danger by the following morning. A jury-rigged antenna allowed an SOS to finally get through, and the Swedish ship ss Belos was despatched.

The next day the crew were taken off (and back to the nearby city of Volos, as it happens), while the Captain, First Officer and Chief Engineer stayed on board for another three days to prevent any attempt to claim salvage rights until recovery operations could be arranged and completed.