Editor-in-Chief of the Underwater Photography Guide NIRUPAM NIGAM went for a dive in the Gulf of Maine, a body of water historically known as “the breadbasket of North America” – only now, as he reports, it’s empty. He took photos anyway

As a child, I was lucky enough to spend my summers with my grandparents in the north-eastern US state of Maine (aka Vacationland).

This meant hot, humid days exploring lighthouses along a rugged coast, the occasional thunderstorm and plenty of lobster rolls. Pungent fish-markets with equally pungent people were always stocked full of crabs, monkfish, haddock and lobster – sometimes as cheap as $4 a pound!

With their mountains of ice and proximity to the North Atlantic fishing fleet, these markets have deep-seated history stretching back before 16th-century European settlement in North America – a time when cod remained supreme in the seascape.

But as the winds of time lap up against North Atlantic shores, the cod have become overfished and replaced by other, lesser species. By 1992, Atlantic cod populations reached 1% of their historical levels, never to recover.

After returning to the region with experience working as a fisheries scientist, I began to notice an interesting trend… the distribution of fish in the markets looked a lot different from my childhood.

If you walk into a Maine fish-market now, you’ll see a lot more foreign species as well as fish that you would never expect to be edible. Take the sea robin. Last month, I visited a market filled to the brim with these rather odd-looking, bony creatures. A little chalkboard perched up next to their icy bodies simply stated “for stews”. Clearly the choice fish have all since swum away.

It was on this recent venture to New England that I was invited to tour the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution – a world-renowned centre for ocean research and the home of the HOV Alvin.

While speaking to the lead scientist at the Fisheries Oceanography & Larval Fish Ecology Lab, I learnt something that struck me as alarming. Experimental fisheries were being set up far off the coast of New England in search of new fishing grounds in the mesopelagic or twilight zone.

That’s when I knew that the health of New England fisheries was definitely in dire straits. Fish in the twilight zone are small, gooey and few and far between. When I posed the question: “Why would anyone fish out there?”, I received a chilling response: “That’s the next place to fish once we fish out everything along the coast. It hasn’t been very profitable.”

This revelation left me itching to get myself and my camera below the cold, grey, temperamental waters of the North Atlantic. I wanted to see this ancient seascape for myself before it was fully exploited – a seascape that has sustained North America for centuries.

After a four-hour drive up the coast to the Gulf of Maine and a bout of Covid, I met up with two dive-buddies who were finishing up their doctoral research at the University of Maine.

“Don’t get your hopes up,” they said, “there’s not much to see around here.” On any given dive, they told me, they saw only a few fish and perhaps a lobster. In fact they were studying what happens to algal populations after all the cod have been fished out and the urchins have been shipped off to Asia. Apparently, all that’s left is a lot of seaweed.

We pulled into Twin Lights State Park in Cape Elizabeth, trunks packed with dive gear. A chilly ocean breeze hit my face as I opened my car door. I noticed a decrepit old lighthouse saddling a cliff overlooking the Atlantic. “That’s it,” my buddy said, “the dive site is underneath that lighthouse.”

Thankfully the swell was calm – one wrong step on the rocky shore could have meant a hard fall with a lot of equipment and heavy camera gear.

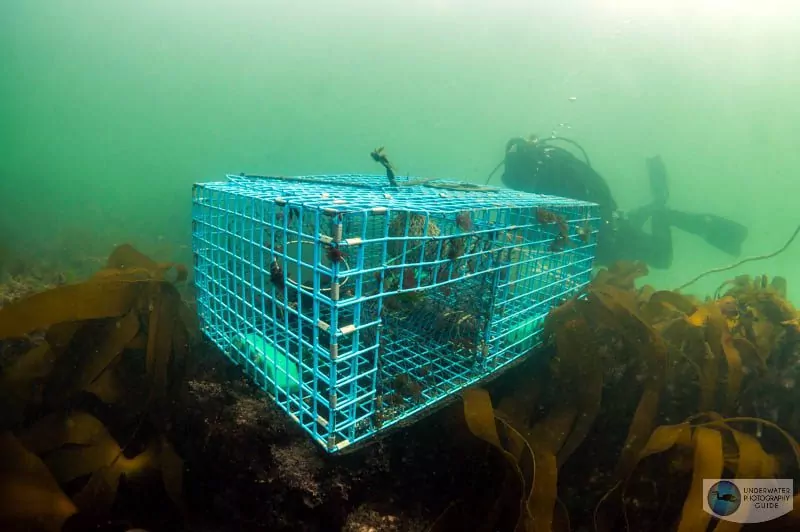

After donning thick fleece undergarments and drysuits, we entered the chilly 5.5°C water and steadily back-kicked out to sea. As I swam, I noticed a string of buoys that followed the contour of the coast. The water was shallow, so I dipped my head under to see strings of lobster traps. All of them were empty.

As we drifted over the dive-site, we gave each other the OK and descended into green, murky depths. The rocky terrain below formed ridges that traversed deeper and deeper out to sea. Following one of these ridges we swam, waiting for critters to pass by.

We swam and swam… and swam. Occasionally, we would see a small crab among beds of seaweed or a jellyfish floating through the water. Invasive vase tunicates (Ciona intestinalis) coated the sea floor. But the seascape was otherwise barren, and an eerie calm percolated through the ocean.

Most disturbingly, during our full 70-minute dive – long by most people’s standards – I saw only one fish. It was a small, unassuming sculpin, well-camouflaged among the seaweed.

In my 12 years of diving experience around the world, I had never been on a dive with just one fish. It’s the equivalent of walking through a forest but seeing only one tree. Or witnessing the last bison standing solitary in the Great Plains. The North Atlantic is witnessing the biological end of an era.

Now don’t me wrong. There is some seasonality when it comes to fish or lobster populations. But I have dived in other regions of the North Atlantic and the Arctic Ocean. Even in traditional Norwegian fishing ports, I have seen thousands more pollack, cod and haddock than I saw that day in the Gulf of Maine. It’s the ocean. There should be plenty of other fish in the sea.

In my days spent collecting fisheries data for the National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), it was easy to get lost in the numbers. The catches I saw landed would turn into data-sheets to be filed away in a far-off government office. It’s easy to forget that those millions of pounds of fish on our data-sheets are real events, in the real world.

They translate to empty oceans. And, for an underwater photographer, it translates to a lack of photo subjects.

North Atlantic cod stocks might be a lost cause. After all, they are a case study for what scientists call the “vortex of extinction”. But perhaps these photos can remind us of what is at stake in the rest of the world if we don’t take a hard look at our industrial fishing practices. So take a look at these empty photos. They are a reminder of what was, and what can be.

There’s Always Something You Can Do

Here are a few things I learnt that can stop the rest of the world from becoming the Gulf of Maine:

- Swim without sunscreen. Sunscreen hurts coral

- Pick up trash. There’s a lot of it

- Take a picture of a fish, but not too many

- Know where your seafood comes from. Buy from sustainable fisheries. Use the Marine Conservation Society’s Good Fish Guide

- Eat farmed bivalve shellfish. It’s even better for the environment than going vegetarian. Just ask Ray Hilborn

- Eat baitfish, such as sardines and anchovies. It’s better for the environment than eating other fish

- Don’t eat shark-fin soup

- Harvest as much as you need (within legal limits) but not more

- Try to keep off the bottom when you’re diving. Use a finger on a rock for stability

- Dive locally as far as possible

- Support artificial reefs such as shipwrecks

- Keep pets away from tide pools (you’d be surprised what they can eat)

- Hang out at the beach. The more people there, the more people care

This article originally appeared in Underwater Photography Guide

Underwater photographer and fisheries scientist Nirupam Nigam grew up in Los Angeles and started his diving in the Channel Islands. He works as a fisheries observer on boats in the Bering Sea and North Pacific and, when not at sea, travels with his fiancée taking photos. His website is Photos From The Sea.