The world’s oceans are estimated to contain 3 million wrecks of ships, submarines and aircraft yet only some 1% have been explored to date.

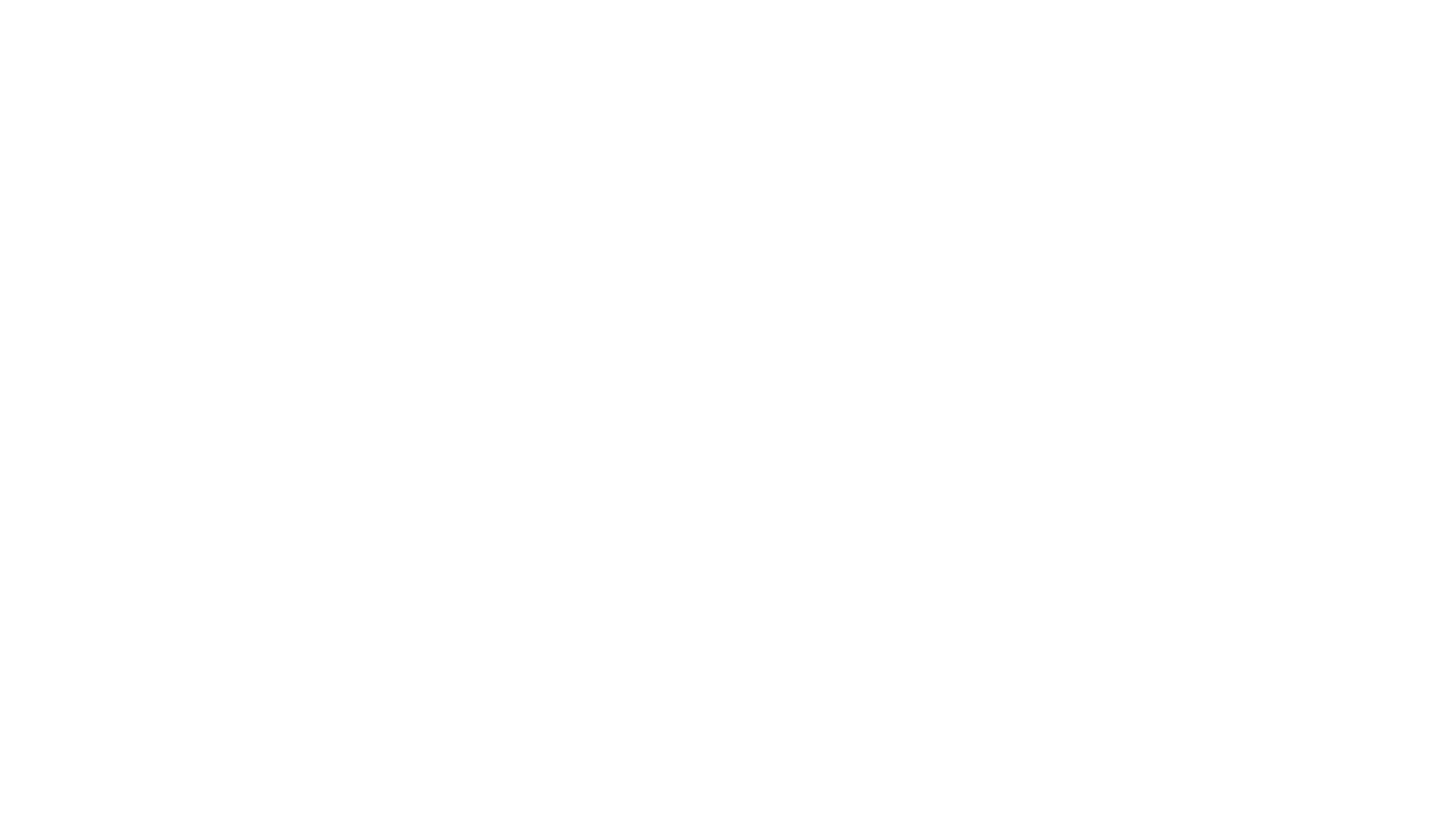

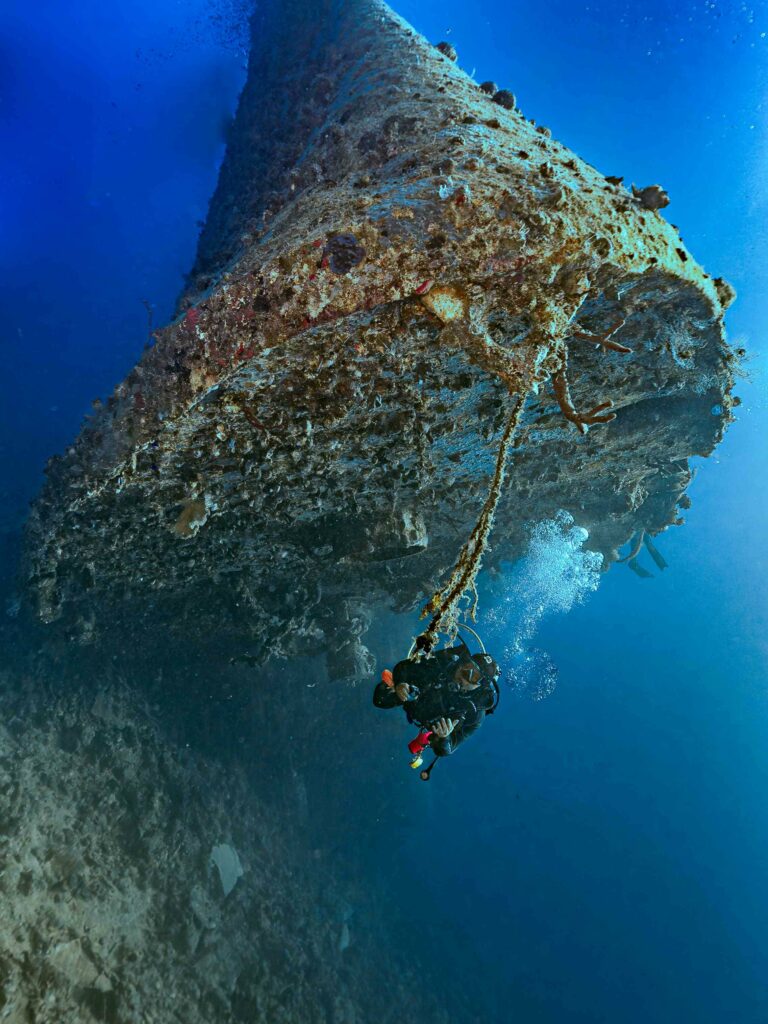

Scuba diving gives divers a sense of adventure as they visit what is hidden from most people’s view.

Malta-based technical diver DANIEL XERRI reflects on other reasons why divers enjoy exploring wrecks so much – while JON BORG’s photography also helps to answer that question.

Also read: World dive record as chilled model poses five times deeper

Seeing what few see

Once a vessel has slipped beneath the waves, only a relatively small number of people will get to see it again up close. The huge depths at which many wrecks are found means that once a discovery is made, it is possible to visit only by using crewed submersibles, remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), or autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs).

This is the case, for instance, with the recent discovery of Ernest Shackleton’s Endurance, which lies beneath 3km of water.

Despite the limitations of human physiognomy, scuba diving provides us with the opportunity to visit a small portion of the existing number of wrecks. The diversity of wrecks found within recreational diving limits boosts the excitement associated with this sport because it enables us to physically explore what non-divers will never get to see, other than through a photograph or video.

Many people are familiar with Jacques Cousteau, and some of them might have watched a documentary detailing his exploits on the ss Thistlegorm, for instance, but it is only by diving on this famous wreck in the Red Sea that one can fully appreciate its magnificence.

Technical diving opens even more levels of exploration because it enables divers to examine those wrecks that lie deeper still. One of the reasons I undertook technical-diving training was to be able to visit the many deep wrecks from the two world wars in the sea surrounding the Maltese islands.

These wrecks are under the stewardship of a national heritage body and divers are able to visit a site as long as they have the required certification and follow best-practice instructions.

Seeing a wreck that has rested on the seabed for several decades emerge out of the darkening blue evokes a kind of excitement that rarely dissipates, irrespective of how many times a diver has visited that particular site.

Diving into history

Wreck-diving enables us to explore sites that have their own place in history. When wreck enthusiasts compare their bucket-lists, many of them seem to agree on the desirability of diving at a small number of famous sites. These most often include Bikini Atoll, Chuuk Lagoon and Scapa Flow.

While geographical remoteness, challenging environmental conditions, depth and expense might make it difficult to achieve some wreck-diving goals, the opportunity to visit certain sites is a means of diving into the past and learning about a vessel that might have played a small role in the history of a country, region or organisation.

This is probably one of the reasons why hundreds of divers visit such historical wrecks as the ss President Coolidge in Vanuatu and the USAT Liberty in Bali annually, while a significantly smaller number execute dives on the HMHS Britannic off Greece.

Even when a wreck has little or no historical value, diving is still a means by which we can connect with its distinct story. In certain cases, this can be quite poignant.

For example, the most famous wreck in Maltese waters is unarguably the Um El Faroud, a 115m-long oil-tanker that is visited by scores of recreational divers every day.

While the fact that it was scuttled in 1998 might lead one to think that there is nothing interesting about this wreck’s story, tragic circumstances lie behind why the Um El Faroud can now be enjoyed by divers.

An explosion that took place while the ship was undergoing maintenance in a dry dock transformed it into a write-off and killed nine shipyard workers.

Even more tragic is the story of Salem Express. The sinking of this passenger ferry in the Red Sea in 1991 led to the loss of more than 470 lives. While diving this wreck is considered controversial in some quarters, those who choose to do so are expected to show utmost respect rather than be driven by mere morbid curiosity.

Interacting with marine life

Wrecks act as artificial reefs, and most often they are teeming with marine life. For example, the first time I descended in Cyprus on the ms Zenobia – a ro-ro ferry that sank in 1980 on her maiden voyage while carrying 108 tractor trailers – I was fully aware of the circumstances of the sinking.

However, nothing prepared me for the well-sized grouper and batteries of barracuda I saw in the first few minutes of the dive.

Some wrecks are famous for acting as a haven for fish, coral and other species, this being one of the prime attractions of the dive-site. For instance, this is probably what makes the ss Yongala the most popular wreck in the southern hemisphere, with around 10,000 divers visiting it every year.

Having already spent more than a century on the seabed, this wreck is a favourite of giant trevally, Maori wrasse, different kinds of ray and turtle and even bull sharks.

The fact that wrecks provide refuge for marine life is an added incentive for divers to visit a particular site. Some countries have sought to capitalise on this phenomenon by scuttling different kinds of vessels, from decommissioned navy ships to severely damaged freighters and tankers.

While the cleaning and scuttling processes must be conducted very carefully to avoid damaging an area’s existing ecosystem, a wreck will eventually attract sea life to it and make it even more attractive for divers.

Nonetheless, when a vessel is scuttled it might take several years for marine life to start colonising it. This was the case with the USS Oriskany – an aircraft-carrier scuttled in Florida in 2006 – and with the USS Kittiwake, a submarine rescue ship scuttled in Grand Cayman in 2011.

Both wrecks have become massively popular with divers and are gradually acting as a home for a wide variety of marine species.

Challenging yourself

Some wrecks have become globally famous not so much for their splendour, history or marine life but for the challenges they pose to those wishing to add them to their list of conquests.

The ss Andrea Doria is perhaps the most infamous example, with entire books having been written about how difficult this Mount Everest of wreck-diving is to explore, and how many divers’ lives it has claimed.

Since sinking in 1956 off the coast of Massachusetts, the wreck has lured hundreds of divers to it, some seeking to recover precious artefacts and souvenirs while others see it simply as a test of their abilities.

Some wreck-enthusiasts become so obsessed that they take huge risks and make significant personal sacrifices to visit a particular site. As recounted in the book Shadow Divers, the discovery and exploration of U-869 took over the lives of US divers John Chatterton and Richie Kohler, who survived to tell the tale but lost so much in the process.

While not all wrecks are so treacherous or challenging that they are suitable only for highly competent technical divers, wreck diving can be a risk-laden activity. This is especially so if one chooses to penetrate a wreck.

The risks of getting disorientated, entangled or running out of air in an overhead environment are not to be underestimated. For this reason, wreck-diving demands a specific set of skills and dispositions.

It is the opportunity to exercise one’s proficiency and mettle as a wreck-diver that attracts some individuals to this activity. When compared to the other attractions of wreck-diving, this might not be the most enticing one; however, some divers derive immense satisfaction from grappling with the potential challenges that a wreck poses.

Follow Daniel Xerri (@daniel.xerri) and Jon Borg (@jonborg) on Instagram

Also on Divernet: Destroyer wreck-dive restrictions lifted, Pushing photo-shoot limits for new world record, Shipwreck silver, brass – even a Model T Ford!, Technically free: a Truk wreck-diving first, Hairy dives but long-lost Alderney wreck ID’d