BALTIC DIVER

In the first of a two-part wreck exploration of the Baltic Sea, with its uncanny powers of preservation, WILL APPLEYARD visits Sweden and Finland

“The water conditions will be cold and dark,” begins the dive-trip briefing emailed to me a week or so prior to my departure for Sweden. And so, with an open mind, I purge my dive-kit bags of warmwater gear, replacing the necessary items with my drysuit, coldwater undersuit, Arctic hood and thick, dexterity-diminishing gloves.

Also read: 2 lions with apple: 17th-century carvings stun divers

Something tells me that this diving trip is going to be Baltic!

The quiet village of Dalarö is a small yet hugely important place for Sweden historically, or for its capital Stockholm at least. The village is pretty, so typically Swedish and, like many other villages within this complex archipelago, is formed of red, yellow, grey or white wooden houses standing neatly behind their white-wood fences.

At a bend in the road, a divers’ hostel and marina sits by the shore, the marina home to small boats that service owners’ holiday homes throughout the islands, together with a cluster of dive-boats.

The islands, at varying distances from the shore, give the impression that one is not by the sea at all but beside a lake, and from the jetty the water is clear, flat and untouched by so much as a breath of wind.

Dalarö was once home to the Swedish maritime customs station, the Tullhuset, built in 1788 and a stopping-point for cargo-carrying sea traffic to Stockholm, which today is just an hour’s drive away.

Maritime activity was at its peak here around the turn of the 18th century. Among these historical buildings is the pilots’ station, once the office for boat pilots selling their services to captains unwilling to navigate these geographically intricate waterways themselves.

A bold few who were unfamiliar with the seaway chanced their luck, resulting in many vessels plunging to the seabed and, over time, creating today’s Dalarö Dive Park.

The Tullhuset is now in part a museum containing artefacts and offering information about the history of the area’s most famous wrecks. The pilots’ office is now a hostel attached to the marina and frequented by visiting divers.

My role here, along with several other dive professionals, is purely to “test-dive” these sites, recently buoyed with tall yellow markers that lead to concrete blocks just off the wrecks.

Seven organisations have been involved with the Baltic wrecks’ protection and promotion, and encompass not only Sweden but also Finland and Estonia.

This exercise in international co-operation is called “Project BALTACAR” (or Baltic History Beneath the Surface). It involves the national heritage boards of Finland and Estonia, the Swedish Maritime Museums, Haninge municipality (which run the Dalarö Dive Park), an Estonian tourism NGO and two private dive-operators in Finland and Estonia.

The project is intended to produce a website (projectbaltacar.eu), publications and public events promoting dive-tourism and maritime history.

The total budget is 1.6m euros, with more than 80% of this provided by the European Regional Development Fund’s “Interreg” Central Baltic Programme. But you’re not expected to remember all that!

Our briefing is held upstairs in the Tullhuset. We’re to dive in two small teams, each one accompanied by a guide – mandatory on many of the most pristine examples of wreckage.

The guides and their respective boat-skippers give an informative briefing, showing off their 3D digital models, running through the dive-plans and points of interest and sharing some historical details of the wrecks themselves.

The first and shallower of the two wrecks is Riksäpplet. It lies at just 14m maximum depth, so requiring a reverse dive-profile.

After the Battle of Öland in 1676, Riksäpplet and her fleet withdrew to Dalarö amid fears of a Danish attack. However, once moved to new anchorage a storm blew up and took the ship to the bottom.

Launched in 1661, the ship is not in particularly great condition for a Baltic wreck, thanks to a destructive salvage operation to recover its valuable wooden remains in 1921.

The purpose of this dive, however, is to ensure that all the divers are comfortable with the cold, dark conditions, and that everybody’s buoyancy is pin-sharp.

Our group will dive twice from the larger cabin-cruiser-style boat Mapas, while group two dives from MAJ, designed for fewer divers, a back-roll entry and local sites.

Baltic shipwrecks are unusually well preserved. This is because salinity is much lower than that of typical ocean water, thanks to an abundance of freshwater run-off. This, together with low oxygen content, provides ideal conditions for timber wrecks.

The brackish water also keeps these wrecks free of shipworm, a clam-like critter that prefers to lay its larvae in saltier water.

After a short motor out, the skipper ties into the yellow buoy and we stride into frigid green water.

Because of the poor condition of this wreck we’re not required to stay with our guide Susanne, so my Swedish buddy and I explore the wooden rib structure and hull remains by ourselves as the rest of the dive-team disperse in different directions.

The wreck is still interestingly recognisable as a boat, its skeletal remains rising 2m or so from the seabed.

I am the only diver wearing wet gloves, and very soon into the dive my fingers begin to complain of the cold.

Operating a camera in such conditions is challenging. The water glows with a bright green hue, yet is very clear, and the low-light conditions make us feel that we are deeper than we are.

It is a perfect site for acclimatising to the water temperature, and even equipped with Arctic-grade diving equipment, it’s difficult for me to stay longer than 35-40 minutes. I decide that the cold will always be the deciding factor over bottom-time or air-consumption here.

We miss the return buoyline and send up an SMB to complete the dive. On surfacing, we find that we’re no more than 5-6m from the buoy and, indeed, the boat.

We lunch back in Dalarö and ready ourselves for the deeper afternoon dive, again only a short ride out from the marina.

This is a showcase dive for the park, on a wreck that has “almost certainly” been identified as Bodekull but is often referred to locally simply as the Dalarö Wreck. Stockholm University believes that this Swedish Navy ship was built between 1659-61 and sank in October 1678. It was carrying flour originating from England or Germany and stoneware Bartman jugs that most likely contained wine.

Had this sinking occurred almost anywhere else in the world, there would surely be nothing left of the ship today.

Bodekull rests just below 30m and the environment is very cold and very dark – potentially a shock to the system, hence the morning breaking-in dive.

Although again, despite these conditions, the water is reasonably clear.

Where the line stops at the seabed, so does the light, and we follow a length of rope until we’re just off the stern.

The wooden hull is the first part of the ship I see and then, peering up and over the top, the decking.

The rudder is still in place and, making our way along the port side, I can just about make out one of two masts still standing proud in the centre of the wreck.

This is a feature unheard of elsewhere in the world of wrecks not even 50 years old.

In single file we follow our guide, who brings us to the bow and to our maximum depth of just over 30m. It is forbidden to fin over the top of this wooden wreck at any point. The guide’s powerful torch-beam reveals the anchor and then a carved wooden lion feature, once the figurehead of the Bodekull.

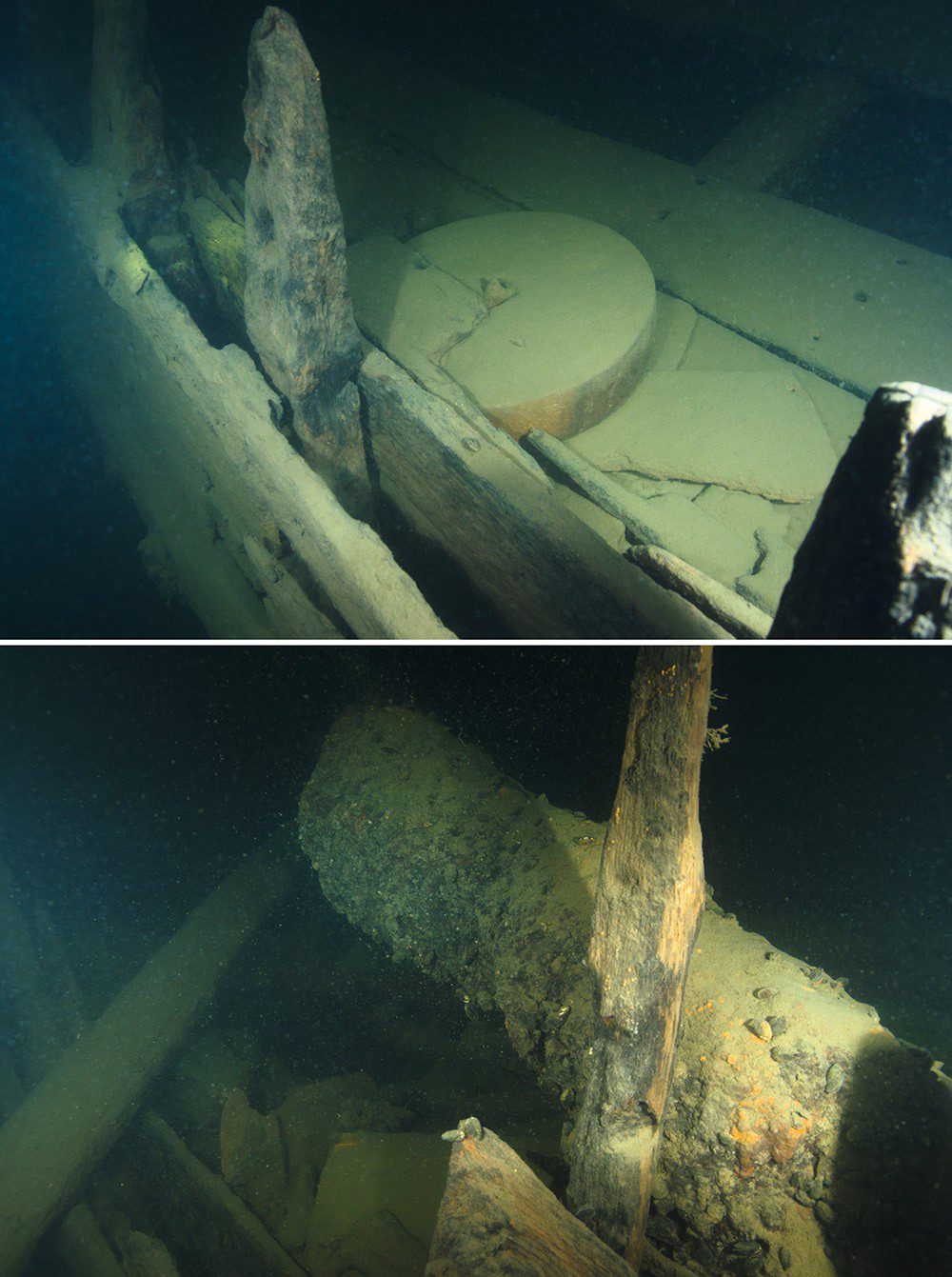

On the starboard side my own torch-beam reveals a circular stone object, now lying flat on the weather deck. This tool, I learn, was used to sharpen knives aboard the boat. It looks as if it had been used only yesterday.

Three or four fin-kicks later and we discover a cannon leaning over the side, still sitting in its carriage, the metal now swollen from centuries under water.

This is the first time I have seen a cannon sitting on the deck of a wreck.

Tools, glass bottles, a musket and a pistol also lie on this side of the deck, giving the impression that the ship sank quickly, with no time for the crew to remove these items before abandoning it.

The wreck is fairly small at around 20m, so it’s possible to make two laps of it on a single tank, although our team took a little longer to absorb all the details and made only one lap, by which time my fingers were frozen solid. Photography is challenging in these conditions, with little in the way of dexterity remaining.

The skipper had earlier explained to me that the best time to dive here was in winter, when the water was nearing 0°. At this time of year, divers are often able to view the whole wreck from stern to bow, he said. During our dive in May, the lowest temperature we hit was 5°C.

The wreck was discovered in 2003 but not made public until 2007, and is one of the finest examples of wreck preservation that I have ever seen.

The diving around Dalarö is challenging, not for the beginner and only for those comfortable with diving in cold and dark conditions, with the equipment to match. For the nautical archaeologist, the experience is top-drawer.

And for me, this kind of trip is the essence of adventure diving.

Effort is required to visit these time capsules, along with a certain amount of discomfort (those fingers again), yet the experience is worth every chilblain.

Those involved in the wreck’s protection are knowledgeable and passionate about this history on their doorstep, and to dive with these people as guides certainly enhances the experience.

My next stop on this Baltic Sea archaeological wreck tour is to be Finland, and I’m curious to discover how this experience will compare to Sweden. So, after a two-week interval, I move on to the town of Hanko on the country’s south-western tip.

Compared with the Swedish trip, the diving in Finland will be relatively shallow, the deepest dive no more than 18m.

I’m pleased to discover that the water is warmer too, at 10°C; balmy compared with the 5°C I had endured in Sweden.

The Swedish, Finnish and Estonian wrecks within the BALTACAR remit are marked with buoys, and any remains deemed to be more than 100 years old are protected by the Cultural Heritage Act.

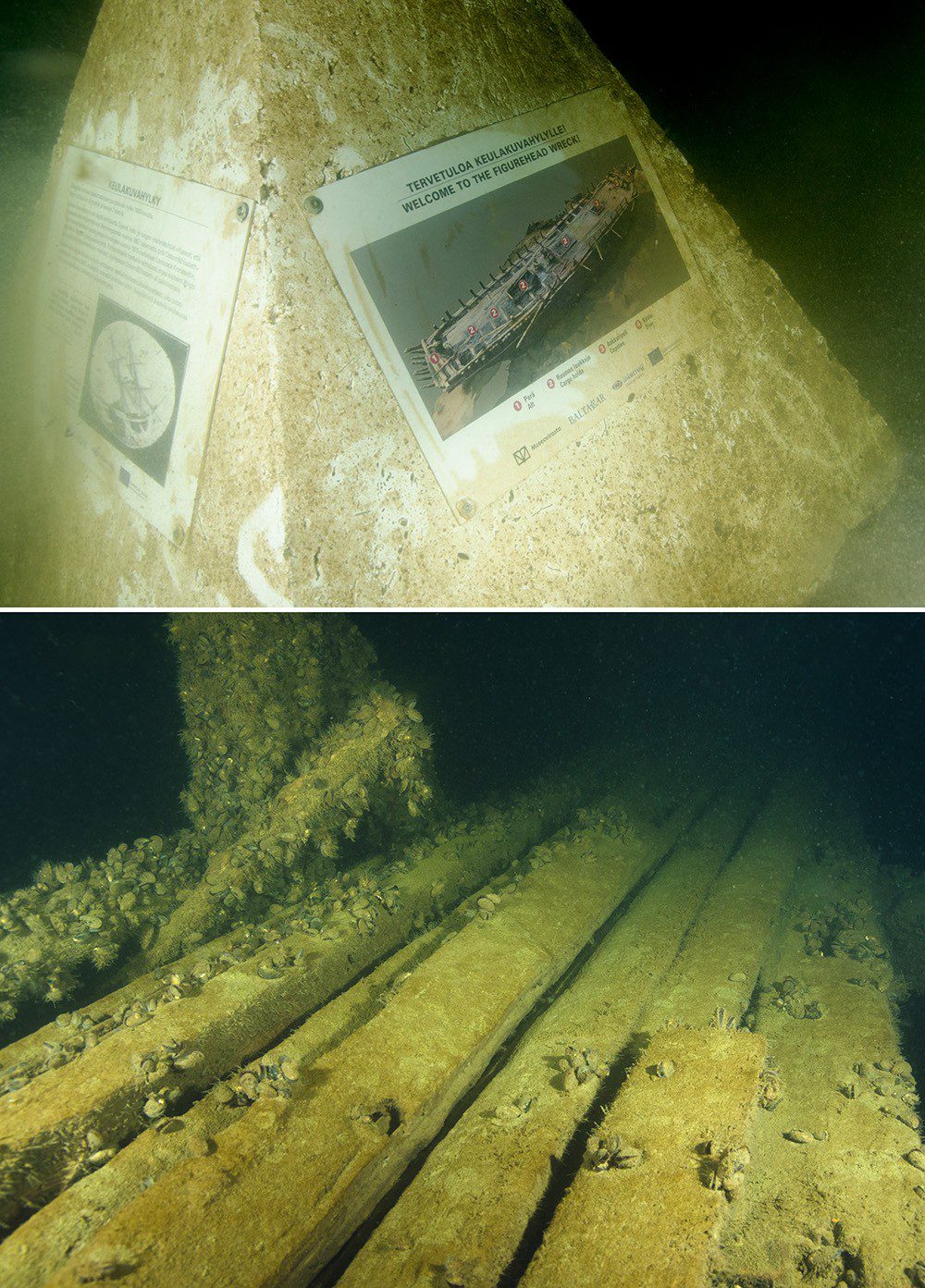

An information board attached to a concrete block marks the beginning of each underwater museum experience in Finland, with detailed maps of the wreck and basic information about its discovery.

Divers will also find the obligatory blurb about “taking only pictures and leaving only bubbles”.

From the concrete block, a line guides Susanne and me to our first wreck, nicknamed “the Figurehead”. We had dived together well on the Swedish trip, so decide to continue with this underwater partnership while in Finland.

My initial nil-visibility woes melt off into the green as we descend, with the water clarity appearing to be vastly better than it had on my initial look from the surface.

Although still fairly dark, both the port and starboard sides of the wreck are visible from the bow on arrival. Only the top 2-3m of water have a soupy look.

The name of the wreck derives from the female-shaped figure that once lunged forward from the bow. This eventually came loose, fell from the wreck and was recovered from the seabed in 2001. It is displayed at the Maritime Centre Vellamo in Kotka, 60 miles east of Helsinki.

Päivi Pihlanjärvi, one of two Finnish underwater archaeologists diving with us, explains to me that the wreck was that of a two-masted sailing ship, 28m long and 7m wide.

“The ship’s history remains somewhat mysterious,” she says. “Its location, size and the details of the frame indicate that it could be the English brig Osborn & Elisabeth, built in Ramsgate in 1857.”

Under Captain Wright and with eight crew aboard, the ship was wrecked during a September storm in 1873, while sailing in ballast from London to the St Petersburg trading port, Kronstadt.

The wreck has kept its three-dimensional shape and sits upright on a seabed of silt that is easy to disturb with poor fin placement. We’re the first divers in the water, so are able to explore the site for the most part on our own.

I’m excited to see that the wooden decking remains in place, except for a few areas in which anchors have levered some of it off prior to mooring-lines and concrete blocks being installed.

I’m enjoying the dive immensely as, from the starboard side, we fin over and across the wreck and peer into the dark cargo-holds with our lights.

We discover the huge wooden rudder still in place at the stern, and then follow the portside hull back towards the bow, where we find the rest of the team now descending the mooring line.

As it’s a shallow dive and the wreck is only 28m long, we’re able to complete three laps before our ascent to make a 5m stop on the line.

The dive-boat above tugs at the heavy mooring chain as we wait, with the wind beginning to pick up at the surface.

Back aboard via the stern ladder, we find a buffet of fruit and biscuits laid out for returning divers, who are all thrilled to have been able to explore a timber wreck in such great condition.

A second dive-boat appears and ties into our stern, politely waiting for the balance of our team to surface before the divers descend.

Any more than 8-10 divers on this wreck would certainly feel overcrowded.

I learn from the locals in our dive-team that visibility can vary from what I considered to be fairly good for this depth on the day to no more than 1-2m.

And so, with a fabulous first dive under our belts, we make for our next Finnish Baltic Sea relic – the Garpen.

I learn from the locals in our dive-team that visibility can vary from what I considered to be fairly good for this depth on the day to no more than 1-2m.

And so, with a fabulous first dive under our belts, we make for our next Finnish Baltic Sea relic – the Garpen.

• In Exploring Baltic Shipwreck in Finland and Estonia, Will’s adventures will continue in Finland before he moves on to Estonia.

FACTFILE (Sweden)

GETTING THERE> Will flew with Norwegian Air to Stockholm. A taxi from there to Dalarö costs £100 but the skippers plan to arrange transfers soon.

DIVING> Mapas, Captain Anders Toll, divecharter.se. MAJ, Captain Krister Jonsson, dykbaten.se

ACCOMMODATION> Divers Hostel (above), vandrarhemmetlotsen.se

WHEN TO GO> Algae blooms in July and early August, so best visibility is September-November and March-May.

MONEY> Swedish krona.

PRICES> Return flights from London from £86. The diver’s hostel has rooms (two sharing) at 700 krona (about £60) a night, or book all 12 beds for a group for 4400 krona. A one-day dive-trip (two wreck dives) with lunch costs from 900 krone pp with Divecharter, dykcharter.se

VISITOR Information> visitsweden.com