Privileged access to premium dive-sites can arouse envy, and one jealous diver tried to put a spoke in tech diver STEFAN PANIS’s La Morépire diving project. However, exploring this spectacular disused slate mine in Belgium for the first time would bring his team light at the end of the Covid tunnel – read his richly illustrated report

At the end of 2020, in the throes of the Covid pandemic, the Belgian “museum mine” La Morépire was forced to close its dry section to guided tours. This gave its owner, Yves Crul, invaluable breathing time to carry out various projects.

Also read: Shipwreck silver, brass – even a Model T Ford!

I had been working on a documentary project with the nearby communities of Bertrix and Herbeumont, so one of the town mayors introduced me to Yves, who is a super-enthusiast for mines – especially slate mines.

We were given the green light to dive and document the mine, though we were granted only a short time-window in which to do so. This would be a one-off opportunity to dive the site, and I was only too grateful to take it with my Mine Exploration Team. We arranged to start as soon as possible.

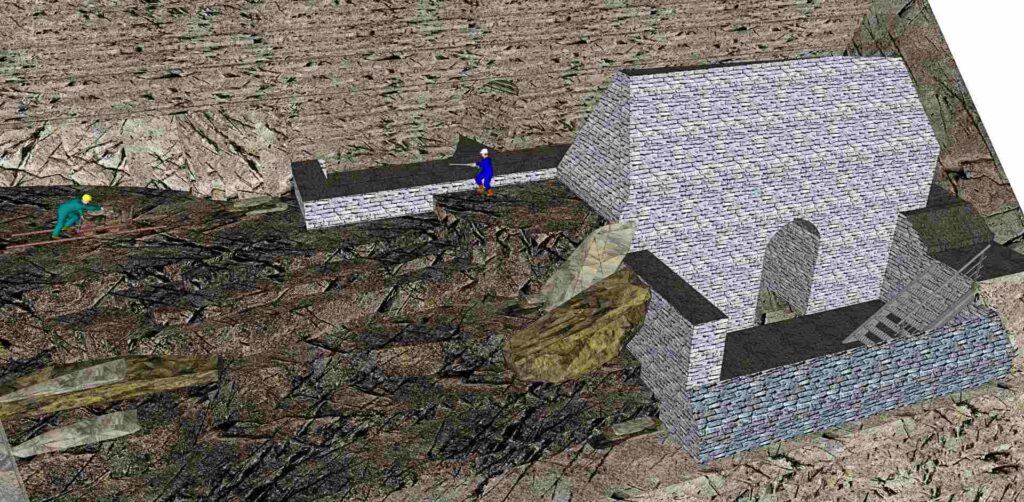

In return for being allowed to dive La Morépire, we would have to produce a 3D topographic model of the site and present Yves with any photos and video footage for use in the museum, which was to be rebuilt over the next year.

The mine, located in Rue du Babinay, Bertrix in the southern Belgian province of Luxembourg, is now open again, and for 9.50 euros anyone who wishes to do so can tour the dry area. Diving is no longer possible, however – so please don’t bother Yves with requests!

During our exploration, a jealous diver got wind of our project and posted false information on social media that anybody could dive there simply by calling the museum – presumably hoping that, inundated with calls, Yves would call a halt to our project.

Fortunately, both he and the mayor were able to pinpoint the guy, and he was reported to the authorities.

The history of La Morépire

La Morépire can be traced back a long way, at least as far as 1836. That was when it was sold to the Perlot family, a big name in slate-mining history that owned several concessions in Belgium.

At its height, 70 miners were extracting ardoisière, as the slate is called, from three levels. At the end of every shift, a supervisor would assess the next areas to be mined and holes were drilled in which to place explosive charges. The last team out would detonate them, and the corridors would be filled with dust – but it would have settled by the next morning.

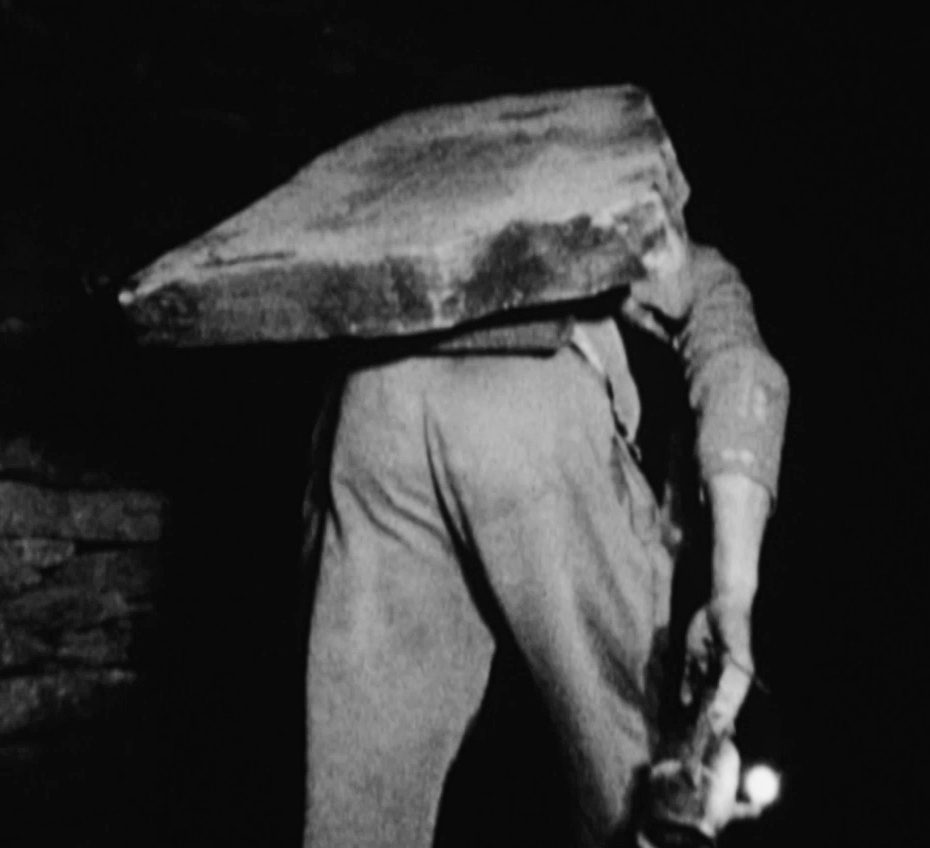

Blocks of slate averaging 100kg were carved out, and miners would carry these on their backs to the waiting mine-carts. When one was full it would be hauled out of the shaft by the winch-operator to be turned into roof-tiles in the workshops above.

The workers were proud and stubborn. There is a story of one man who carved out an enormous 300kg block too heavy to lift. He exerted himself to the extent that veins in his eyes burst, blinding him – but he still carried that block out!

By 1977, open-air slate mines in Spain and Portugal were delivering much cheaper roof-tiles and eventually La Morépire was forced to close. The pumps were stopped and slowly the groundwater claimed back the mine, filling it to the top.

Yves bought the mine in 1996 and started his Au Coeur de l’Ardoise (In the Heart of the Slate) heritage business. He had to pump non-stop for five months just to get the water down to the 25m level. Even today, it costs about 1,000 euros a month to maintain this level.

Every dive in a “new” mine is special, but when nobody has ever been allowed to dive at a location before, it’s amazingly exciting!

Diving La Morépire

We enter the water down the main shaft, where a long time ago the mine-carts were pulled in and out. When the museum opened, Yves had installed a cart to take the visitors down to the mine on the same rails, but one winter a badger had crawled into the fusebox and caused a short-circuit. That was the end of the lift, because the insurance company had refused to pay.

Yves worked day and night for a week to install 268 stainless-steel steps, allowing him to re-open the museum. The steps go all the way to the water, and the shaft is wide enough for storing stage-tanks and cameras, a luxury for us.

It’s a mighty feeling to descend the shaft for the first time. Only 5m down, we are already facing side-passages to left and right. On the right I spot a beautiful old hand-pump before the passage splits into north and south corridors.

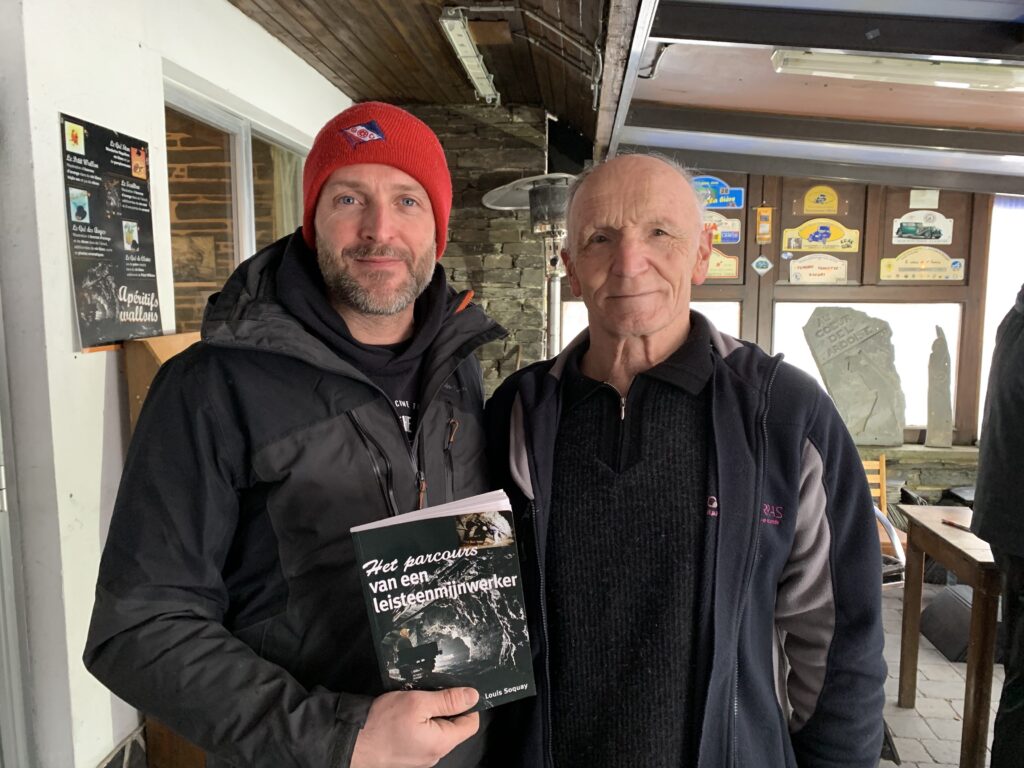

At the end of the left-hand corridor stands a massive timber winch in wood, beautifully preserved, in a huge chamber named the Italian Room. Louis Soquay, an 80-year-old miner we would meet afterwards, told us that it had been mainly Italian immigrants who worked in this part of the mine.

We dive down a 45° slope to take in the impressive sight of a mine-cart still on the rails. At the end of the room the shaft narrows and continues until it levels out at a depth of 37m. Here it turns underneath the main shaft to connect with a chamber from the right corridor at -5m. Falling sediment and zero visibility here leads us to name this shaft the Hellhole!

In the left corridor at -10m we discover many objects, including an old telephone for communicating with the surface. From the plans we know that the first massive chamber can’t be far away, but unfortunately the narrow passage is blocked, and it would cost us too much time to clear the debris.

We move further along the main corridor, and my heart skips a few beats as my torch illuminates – a face! It turns out to be a decorative figure from the museum that has fallen down here through a ventilation shaft.

Just ahead a beautiful mine-cart turntable leads us on to the next extraction chamber. It is awesome to float through this big room and admire the miners’ work.

At the next turn we find steps that surprisingly take us to – the surface! It’s a perfect mid-mine emergency exit should anything go wrong. We start to use our Seacraft-sponsored scooters to cover the distances faster, but are eventually faced with a collapse that appears to have sealed the last chamber forever.

The -10m shaft to the right hold another nice surprise. It seems to be full of debris, and because this was the old part of the mine we assume it was used to stuff anything the miners didn’t need to take back up.

We follow the double rails, and just beyond the turn is another collapse, but because we are diving sidemount we are able to squeeze through. A beautiful corridor leads to a new room, the top of which emerges into an air-pocket, but no connection to the upper dry levels.

The -60m level of the mine proves much harder to negotiate. Louis told us that the old right side was very unstable and that he had never been in there because it was deemed too dangerous.

And as David ties off on the main line, with me hanging in the corridor to let him lead the way, a slate block falls from the ceiling onto my legs, so we decide to go the other way!

At the base of the shaft lie a pile of old wooden ladders. These make me wonder further about the hard work that faced the miners, negotiating ladders with 100kg of stone on their backs. Again our route is blocked, this time by a spider’s web of electricity cables that would be dangerous to try to get through in zero vis, so we decide to turn back and continue on another level.

On the next dive we bring tools to clear the way here and discover some extraction chambers, but our time-window to explore the mine proves too short for us to cover the entire complex.

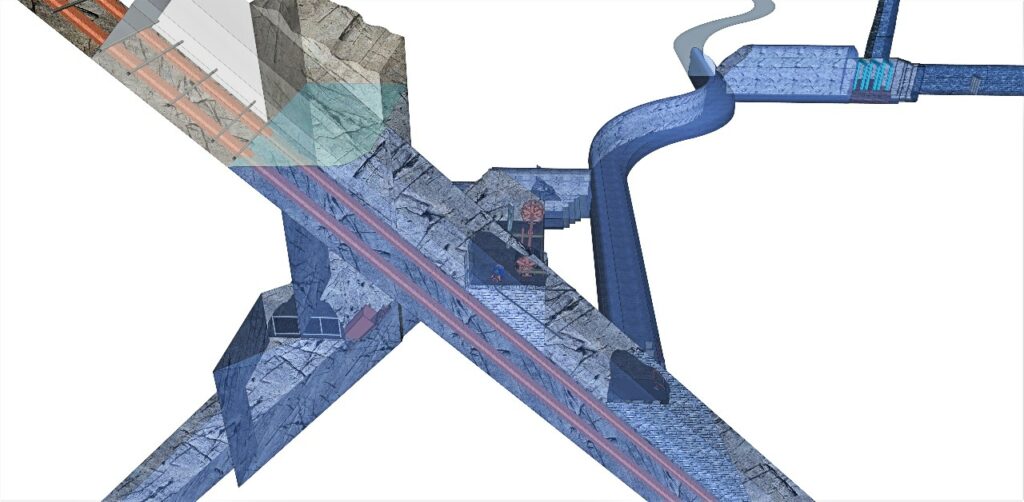

On our first dives a lot of line had been installed to make navigation easier and safer on subsequent dives. Dirk needs a lot of information from the dive-team to complete the map. The main lines are marked at 5m intervals, where we stop to take measurements and bearings and draw a sketch. I also take a still at each point, as well as others of notable features.

On the next dive, Jimmy films everything. This approach takes time, but we know that if it is done correctly the results will be amazing.

On the final dives we have a helpful new tool to use, the Mnemo. Connected to the line, it registers depth, distance angle and bearing, and after the dive the data can be uploaded to a computer and transferred to an Excel file or shown as graphics.

Legacy of the dives

After our dives, we are allowed to document the dry parts of the mine, both touristic and non-public, and marvel at the massive and spectacular chambers. It’s amazing how many tools we still find – drills, hoses and hoists – as well as personal stuff: a coat, gloves or an empty cigarette-packet, a drinking can or a bottle of beer.

Historical pictures are a great addition to a project like this, but as when researching old ship’s pictures, it’s not easy. I usually start with an online search for museums or archives that might cover a mine or mining company, before sending out loads of emails in the hope of some positive response.

Sometimes I have to take time off work and travel to see a collection in person, perhaps 200km away, but one useful picture can make all the effort worthwhile.

In my La Morépire mine quest I am lucky enough to find something unique: a 32-minute documentary made in 1953, with footage both from above and below. It will be amazing to include some of this in our own documentary.

When the museum reopens after its rebuilding a lot of our work will be used in the visitor briefings, including our photos and video footage.

But nice pictures or video are not enough if you take a scientific approach. Dirk’s 3D topographical model will be used as a new safety-plan for the tourist parts of the mine, including escape-routes as well as the points of interest. He has already produced more than 200 hours of drawing work and the result promises to be spectacular.

A final word about Louis Soquay, who is 81 but looks little more than 65, and wrote a book about life in “his” mine. Our long talks were always super-interesting and emotional, and he descended the stairs with us several times to explain something.

Marching through the mine with him made us feel humble and hugely respectful. He and the other miners were brave men indeed.

Also on Divernet: A Tale Of Two Mines, Wondrous Dive Into Black Marble, HMS Brazen Wreck Dive, Monarch Of The Channel, Pearl Of The Peak District, Diver Article Prompts Wreck-Find Handover